Invasion History

First Non-native North American Tidal Record: 1999First Non-native West Coast Tidal Record:

First Non-native East/Gulf Coast Tidal Record: 1999

General Invasion History:

Perna viridis is native to the Indo-Pacific, from the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Thailand, south through Indonesia. It has been introduced to several parts of the world, including China and southern Japan, Polynesia, the Caribbean (Venezuela-Jamaica), and the southeastern US from the Gulf Coast of Florida north to the Carolinas (Agard et al. 1992; Iwasaki 2006; Baker et al. 2007). Genetic analyses suggest that there was a single introduction of a small population to the Western Atlantic (Gilg et al. 2013). Sporadic records are known from northern and western Australia (Baker et al. 2007; Stafford et al. 2007; McDonald 2012). It has been reported from South Africa, with no location, and no information on establishment (Mead et al. 2011). This mussel is easily transported in ship fouling, as larvae in ballast water, and also by official and unofficial planting as seafood (Baker et al. 2007; Rajagopal et al. 2006).

North American Invasion History:

Invasion History on the East Coast:

Although a few isolated dead specimens were found in Virginia Beach, Virginia (VA) in 2001, P. viridis was first reported to be established on the East Coast of the US at Ponce de Leon Inlet, at the north end of the Indian River Lagoon in October 2002 (USGS Nonindigenous Species Program 2002; Baker et al. 2007). In 2003, it was collected from Pablo Creek, Florida (FL) (south of St. Augustine) north to the Savannah River, Georgia (GA) (USGS Nonindigenous Species Program 2003; Power et al. 2004; Baker et al. 2007), and several dead specimens were found at Oregon Inlet, North Carolina (NC). Green Mussels were reportedly abundant as far north as Mayport, FL, at the mouth of the St. Johns River estuary, and seasonally common as far north as Charleston, South Carolina (SC) (Baker et al. 2007). In coastal waters, the northernmost established population is in the St Mary’s River, on the FL-GA border, while a population on an offshore artificial reef off Brunswick, GA probably owes its persistence to the Gulf Stream (Power et al. 2004; Baker et al. 2007). Perna viridis appears to be at its northern range limit in northern Florida - in experiments, it suffered 94% mortality over a 20 day exposure to 14ºC seawater (Urian et al. 2011). Dramatic die-offs were observed during the winters of 2010 and 2011 near St. Augustine, FL (Matthew Gilg, cited by Edwards 2011).

Invasion History on the Gulf Coast:

Perna viridis was first reported in US waters in Tampa Bay, Florida (FL), in 1999, when it was found to be fouling power plants there. At the time of its discovery, it had already colonized shores north (Treasure Island, Anclote Key) and south (Sarasota Bay, Charlotte Harbor) of Tampa Bay (Benson et al. 2001; Ingrao et al. 2001; Baker et al. 2007). Its range expansion on the northern shore of the Gulf has been limited to sporadic occurrences of a few specimens near Pensacola Bay, FL (2002), Panama City, FL (2008), and Perdido Bay, Alabama (Baker et al. 2007; USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2011). It has expanded its range southward towards the tip of Florida, reaching Naples (2001) and Marco Island (2003) (Baker et al. 2007). Its establishment is uncertain in Florida Bay, but one specimen was found in netting attached to the beak of a sawfish (Pristis pectinata) (Baker et al. 2007). The abundance and range of this tropical mussel in southeastern US waters fluctuates greatly with the severity of winter weather. At low tides in the winter of 2008, P. viridis was exposed to air temperatures below 2ºC for periods of 6 h or more, while water temperature remained around 20ºC. This was accompanied by extensive mortality. Subsequent winters (2009, 2010), were also accompanied by severe mortality (Firth et al. 2011). In the northern and western shore of the Gulf, water temperatures below 14ºC may also limit survival (Urian et al. 2011). Attempts to obtain P. viridis for SERC experiments in 2011 from Tampa Bay were unsuccessful. Local researchers said that they were virtually absent from areas where they had been abundant several years earlier (Joao Canning-Clode, personal communication 2011). However, warming of the climate is likely to result in northward range expansion, with fluctuations due to occasional severe winter weather (Firth et al. 2011; Urian et al. 2011).

Invasion History Elsewhere in the World:

Perna viridis was first reported in the Western Hemisphere in Trinidad, on the Caribbean Sea in 1990 (Agard et al. 1992). By 1993, they had colonized Isla Margarita, Venezuela and the Venezuelan mainland, where they displaced established populations of P. perna (Segnini de Bravo et al. 1998; Perez et al. 2007). In 1998, they became established in Kingston Harbor, Jamaica (Buddo et al. 2003; Baker et al. 2007). Across the Atlantic, a deliberate introduction was made for aquaculture in the Cape Verde Islands in 1994, using mussels from China, but by 2004, none of these mussels had survived (Baker et al. 2007).

In the Pacific, Perna viridis was first reported from Japan in Tokyo Bay in 1967, and subsequently appeared in other ports (Osaka, Nagoya) where it was dependent on thermal effluents for winter survival. A warming climate may have permitted it to become established in Sagami Bay, and the Seto Inland Sea (Uemori and Horikoshi 1991; Ueda 2000; Iwasaki 2006; Baker et al. 2007). It has spread to other Asian coastal waters, including Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean, and Japanese waters of the East China Sea, Hong Kong, Hainan, and the Ryukyu Islands of Japan (Huang 2001; Iwasaki 2006; Baker et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2010). In northern Australia, P. viridis appeared in Trinity Inlet, Cairns (Queensland) in 2001. It was found on vessel hulls, buoys, and test substrates as late as 2004, but is 'presumed to be eradicated or died out' (Baker et al. 2007; Stafford et al. 2007). In a review of occurrences in Australia, there is no evidence of establishment, despite the arrival of hundreds of fouled ships, and modeling that indicated that northern Australia was a favorable environment. Bayesian analysis suggests that the probability of establishment is much lower than originally thought (Heersink et al. 2019).

Description

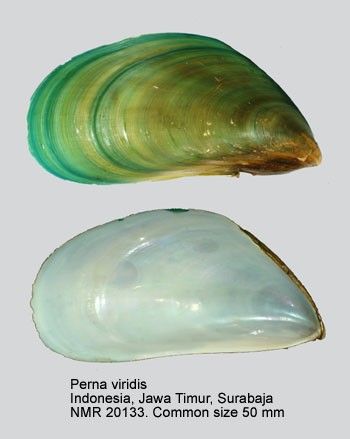

Perna viridis is roughly oval in shape through its ventral region, but gradually curves to a more triangular shape in its dorsal half, with an apex at the hinge. The beak of the shell is downturned. The shell is narrower in the anterior-posterior direction than that of P. perna, and the ventral margin is concave. The anterior retractor muscle leaves a 3-part scar in Perna, as compared to a continuous, elongated scar in Mytilus. In live animals, P. viridis has less pronounced papillae along the mantle margin than P. perna. Juveniles of P. viridis are typically marked with brilliant green and red, while adult shells are less bright, and have more brown. In adults, abrasion removes the periostracum, leaving white or pink patches (Siddall 1980; Rajagopal et al. 2006). Larval morphology is described by Siddall (1980). The larvae settle at ~215 µm (Siddall 1980), after about 13 to 41 days in the plankton (Manoj Nair and Appukuttan 2003) and become mature at a shell length of 15-30 mm (Ingrao et al. 2001). They can grow to 168 mm in length, but more usually to 80-100 mm (Agard et al. 1992; Benson et al. 2001). Because morphological characteristics are variable, and somewhat overlapping, Ingrao et al. (2001) used chromosomes to distinguish species - P. perna has 14 homologous pairs, while P. viridis has 15. Molecular identification (mitochondrial DNA) was used by Benson et al. (2001).

Taxonomy

Taxonomic Tree

| Kingdom: | Animalia | |

| Phylum: | Mollusca | |

| Class: | Bivalvia | |

| Subclass: | Pteriomorphia | |

| Order: | Mytiloida | |

| Family: | Mytilidae | |

| Genus: | Perna | |

| Species: | viridis |

Synonyms

Chloromya viridis (Dodge, 1952)

Mytilus opalus ( Lamarck, 1819)

Mytilus smaragdinus (Chemnitz, 1785)

Mytilus viridis (Linnaeus, 1758)

Perna viridis (Ahmed, 1974)

Potentially Misidentified Species

None

Perna perna

None

Ecology

General:

Perna viridis has separate sexes and animals mature at 1 year of age or less. This species has a prolonged spawning season, and in some tropical regions, spawns year round (Barber et al. 2005). Fertilized eggs develop into a planktonic trochophore larva, then into a shelled veliger. The larvae settle at ~215 µm (Siddall 1980), after about 13-41 days in the plankton, and become mature at a shell length of 15-30 mm (Manoj Nair and Appukuttan 2003; Rajogoppal et al. 2006). Field collections in the Intracoastal Waterway, Florida, indicate that most larvae settle within 5 km of the parent population, but modeling suggests that some could disperse as far as 100 km (Gilg et al. 2014).

Larvae of P. viridis can settle and metamorphose on a wide variety of surfaces, including rock, wood and mollusk shells. As they grow, they are attracted to other mussels. Extensive beds develop on rocky surfaces, but also on soft sediments, in which mussels are connected to each other and the substrate by byssus threads, creating a complex habitat (Buschbaunm et al. 2009). Mussels are strong-filter feeders, and create substantial currents as they pump in water to ingest phytoplankton and other suspended material. They deposit the uneaten material as pseudofeces, creating deposits of silt around and within the mussel bed (Bertness 1999; Buschbaum et al. 2009).

Green Mussels are characteristic of shallow subtidal and lower intertidal zones, and can be subject to sharp changes in temperature when exposed to the air and changes in salinity due to rainfall and river flow. Adult P. viridis can feed and grow in salinities of 19-58 PSU (Rajogopal et al. 2006; Baker et al. 2007). With a closed shell, they can survive up to 11 days in fresh water without feeding (Segnini de Bravo et al. 1998). The salinity range for successful larval development is narrower (25-35 PSU, Romero and Romeira 1981). Perna viridis' temperature range in water is ~12-14 to 32.5ºC (Benson et al. 2001; Rajagopal et al. 2006; Urian et al. 2011). Its degree of tolerance to cold air exposure is limited, and exposures of several hours to temperatures of 0-2ºC at low tide were followed by high mortality (Firth et al. 2011). Spawning has been reported over a range from 18 to 31.3ºC, but larval development is optimal at about 29ºC (Barber et al. 2005; Rajagopal et al. 2006). Spawning in Indian populations is often triggered by a drop in salinity to about 20 PSU (Rajagopal et al. 2006), but salinity of 36 PSU is considered optimal for larval development (Manoj Nair and Appukuttan 2003).

Food:

Phytoplankton, detritus

Consumers:

crabs, fishes, snails

Competitors:

Perna perna, Mytilus galloprovincialis

Trophic Status:

Suspension Feeder

SusFedHabitats

| General Habitat | Coarse Woody Debris | None |

| General Habitat | Oyster Reef | None |

| General Habitat | Marinas & Docks | None |

| General Habitat | Rocky | None |

| General Habitat | Mangroves | None |

| Salinity Range | Polyhaline | 18-30 PSU |

| Salinity Range | Euhaline | 30-40 PSU |

| Salinity Range | Hyperhaline | 40+ PSU |

| Tidal Range | Subtidal | None |

| Tidal Range | Low Intertidal | None |

| Vertical Habitat | Epibenthic | None |

Life History

Tolerances and Life History Parameters

| Minimum Temperature (ºC) | 12 | Field data (Benson et al. 2001; McFarland et al. 2015). Experimental studies found increased mortality at or below 14 C, with ~50% survival for 12 days at 14 C (Urian et al. 2010). |

| Maximum Temperature (ºC) | 32.5 | Field data (Rajagpopal 2006; McFarland et al. 2015) |

| Minimum Salinity (‰) | 6 | Perna viridis tolerated gradual decreases in salinity with 40-50% survival over 50 days (McFarland et al. 2015); Segnini de Bravo et al. (1998) reported a much wider salinity range (0-64 PSU), by exposing animals to more rapid changes (2 PSU changed/every 2 days), but without previous acclimation. Most of the animals survived for 11 days with no mortality in freshwater (Segnini de Bravo et al. 1998). However, they did not report whether feeding occurred. Mussels survived at and fed at 25 PSU, but did not feed, and died within 120 hours at 10 and 15 PSU (McFarland et al. 2013). |

| Maximum Salinity (‰) | 58 | Field, Venezuela (Segnini de Bravo et al. 1998) |

| Minimum Reproductive Temperature | 18 | Field data, spawning adults November, Tampa Bay (Barber et al. 2005) |

| Maximum Reproductive Temperature | 31.3 | Field data, spawning adults, India (Rajagopal et al. 2006) |

| Minimum Reproductive Salinity | 20 | Spawning in Indian populations (Rajagopal et al. 2006) |

| Maximum Reproductive Salinity | 38 | Manoj Nair and Appukuttan 2003 |

| Minimum Duration | 13 | Manoj Nair and Appukuttan 2003 (29 C) |

| Maximum Duration | 41 | Manoj Nair and Appukuttan 2003 (29 C) (24 C) |

| Minimum Length (mm) | 15 | Maturation at 15-30 mm (Ingrao et al. 2001). |

| Maximum Length (mm) | 168 | Agard et al. 1992, but more usually, 80-100 mm (Benson et al. 2001; Rajogopal et al. 2006). |

| Broad Temperature Range | None | Warm-temperate-Tropical |

| Broad Salinity Range | None | Polyhaline-Euhaline |

General Impacts

Perna viridis is a potential ecosystem engineer, a major fouling organism, and also a valuable human and wildlife food sources in its native and introduced ranges (Rajagopal et al. 2006; Baker et al. 2007). Consequently, its economic impacts are complex. In subtropical-warm-temperate regions of Asia and the southeast US, the range, abundance, and impacts of P. viridis are likely to fluctuate with episodes of severe winter weather (Baker et al. 2007; Firth et al. 2011; Urian et al. 2011). Baker et al. (2007) note that as an invader in diverse tropical marine systems, it increases the amount and costs of fouling impacts on industry, shipping, and fisheries, but unlike the Zebra Mussel, does not create novel fouling problems, where none or few previously existed.

Economic Impacts

Industry- Perna viridis is a major fouling organism of power plants in India, Japan, and in Tampa Bay, and probably in other coastal locations. The economic and environmental costs of chemicals used to control P. viridis and other fouler must be added to costs of increased cleaning and shutdowns of power plants (Ingrao et al. 2001; Iwasaki 2006; Rajagopal et al. 2006). This mussel also affects other users of seawater- it blocked the seawater system of Mote Marine Laboratories in Florida (Ingrao et al. 2001).

Shipping- Perna viridis is a frequent fouler of piers, jetties, buoys, and ships’ hulls (Baker et al. 2004; Rajagopal et al. 2006; Baker et al. 2007). As with industrial uses, the economic costs and toxic effects of antifouling paints should be considered as part of this mussel's economic impact.

Fisheries- Perna viridis is a desirable seafood species and is widely cultured in India, Malaysia, and the Philippines. It reaches marketable size in less than six months, compared to 1-2 years for temperate Mytilus spp (Rajagopal et al. 2006). It has been successfully introduced for culture in Tahiti and New Caledonia, but attempts at aquaculture in Samoa, Tonga, and Fiji were unsuccessful (Eldredge 1994; Baker et al. 2007). This mussel is commercially harvested in Venezuela (Segnini de Bravo 2003). However, it also fouls oysters and other commercially cultured and harvested shellfish (Baker et al. 2004; Chavanich et al. 2010). A major concern for human consumption, as with other bivalves, is accumulation of toxic pollutants, and 'red tide' toxins from phytoplankton, which may restrict harvesting (Buddo et al. 2003; Rajagopal et al. 2006; Buddo et al. 2012).

Ecological Impacts

Competition- In Venezuela, Perna viridis appeared to be replacing the previously introduced P. perna (Brown Mussel), possibly because of its greater environmental tolerances (Segnini de Bravo et al. 1998). In Tampa Bay, P. viridis was common on oyster reefs, and was reported to cause high oyster mortalities (Baker et al. 2004), presumably through fouling. 'On pilings, green mussels displace oysters to a narrow band in the upper intertidal' (Baker et al. 2004). In experiments, however, oysters had better survival during air exposure at moderate (26ºC) air temperatures than P. viridis (McFarland et al. 2015) and are unlikely to compete with oysters in the intertidal zone. Barber et al. (2005) suggest that P. viridis might be able to out-compete the native Brachidontes exustus (Scorched Mussel) because of the former's faster growth, large size, and greater reproductive output.

Habitat Change- Intertidal mussels are significant ecosystem engineers, creating a structure of shells bound to the rocks and each other with byssal threads, creating surfaces for attachment and sheltered niches for attached and mobile organisms. On unstructured bottoms, mussel beds provide solid substrate where it was previously absent (Bertness et al. 1999; Buschbaum et al. 2010). Perna viridis has invaded mangrove communities, muddy sea bottoms, oyster beds, rocky shores and artificial substrates such as piers, seawalls, canals, and seawater intakes (Buddo et al. 2003; Rajagopal et al. 2006; Baker et al. 2007). However, we have little specific information on how beds of P. viridis affect local biota. In Japan, and probably in the southeast US, winter die-offs of P. viridis can cause hypoxia (Chavanich et al. 2010; Firth et al. 2011; Urian et al. 2011).

Regional Impacts

| NWP-3b | None | Ecological Impact | Competition | ||

| Competition between P. viridis and native benthic fauna is suspected (Chavanich et al. 2010). | |||||

| NWP-3b | None | Ecological Impact | Habitat Change | ||

| Death and deposition of P. viridis in winter may cause hypoxic conditions (Chavanich et al. 2010). | |||||

| NWP-3b | None | Economic Impact | Fisheries | ||

| Fouling of cultured bivalves by P. viridis is suspected to reduce their growth (Chavanich et al. 2010). | |||||

| SP-XVI | None | Economic Impact | Fisheries | ||

| Aquaculture of P. viridis is continuing (Eldredge 1994; Baker et al. 2007) | |||||

| SP-IV | None | Economic Impact | Fisheries | ||

| Aquaculture of P. viridis is continuing (Eldredge 1994; Baker et al. 2007) | |||||

| CAR-III | None | Ecological Impact | Competition | ||

| Perna viridis has been replacing P. perna in Venezuelan estuaries (Segnini de Bravo et al. 1998; Perez et al. 2007). This has been attributed to greater temperature-salinity tolerance in P. viridis (Segnini de Bravo et al. 1998). | |||||

| G070 | Tampa Bay | Economic Impact | Industry | ||

| Perna viridis was discovered when it was found to be fouling Tampa Electric Company Gannon Station Power Plant, and several other power plants in Tampa Bay. This mussel increases the cost of fouling control (Baker et al. 2007). | |||||

| CAR-I | Northern Yucatan, Gulf of Mexico, Florida Straits, to Middle Eastern Florida | Economic Impact | Industry | ||

| Perna viridis was discovered when it was found to be fouling Tampa Electric Company Gannon Station Power Plant, and several other power plants in Tampa Bay. It also blocked seawater systems in the Mote Marine Laboratory, in Sarasota (Ingrao et al. 2001). This mussel increases the cost of fouling control in power plants (Baker et al. 2007). | |||||

| G060 | Sarasota Bay | Economic Impact | Industry | ||

| Perna viridis blocked seawater systems in the Mote Marine Laboratory, in Sarasota (Ingrao et al. 2001). | |||||

| G070 | Tampa Bay | Economic Impact | Fisheries | ||

| Perna viridis is 'abundant on oyster reefs in Tampa Bay, and are correlated with high oyster mortalities' (Baker et al. 2004). | |||||

| G070 | Tampa Bay | Economic Impact | Shipping/Boating | ||

| Perna viridis fouls US coast Guard buoys, threatening to sink them, and requiring increased cleaning efforts (Baker et al. 2004). | |||||

| G070 | Tampa Bay | Ecological Impact | Competition | ||

| 'Green mussels are abundant on oyster reefs in Tampa Bay, and are correlated with high oyster mortalities. On pilings, green mussels displace oysters to a narrow band in the upper intertidal' (Baker et al. 2004). Barber et al. (2005) suggest that P. viridis might be able to out-compete the native Brachidontes exustus (Scorched Mussel) because of the former's faster growth, large size, and greater reproductive output. | |||||

| CAR-I | Northern Yucatan, Gulf of Mexico, Florida Straits, to Middle Eastern Florida | Economic Impact | Fisheries | ||

| Perna viridis is 'abundant on oyster reefs in Tampa Bay, and are correlated with high oyster mortalities' (Baker et al. 2004). | |||||

| CAR-I | Northern Yucatan, Gulf of Mexico, Florida Straits, to Middle Eastern Florida | Economic Impact | Shipping/Boating | ||

| Perna viridis fouls US coast Guard buoys, threatening to sink them, and requiring increased cleaning efforts (Baker et al. 2004). | |||||

| CAR-I | Northern Yucatan, Gulf of Mexico, Florida Straits, to Middle Eastern Florida | Ecological Impact | Competition | ||

| 'Green mussels are abundant on oyster reefs in Tampa Bay, and are correlated with high oyster mortalities. On pilings, green mussels displace oysters to a narrow band in the upper intertidal' (Baker et al. 2004). Barber et al. (2005) suggest that P. viridis might be able to out-compete the native Brachidontes exustus (Scorched Mussel) because of the former's faster growth, large size, and greater reproductive output. Baker et al. (2004) found that P. viridis co-occurred with B. exustus, and may exclude the oyster Crassostrea virginica in some habitats, but its impacts are limited by their preference for artificial structures, and their vulnerability to severe cold and toxic phytoplankton blooms (Baker et al. 2011). In experiments in Mosquito Lagoon, Florida, Perna viridis, on fouling plates, reduced the settlement of larvae of Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica), but did not affect the growth of oyster spat (Yuan et al. 2016). Year-round high reproductive output and high energy reserves indicate a potential for competition with native Eastern Oysters (Crassostrea virginica (McFarland et al. 2016). | |||||

| NWP-3b | None | Economic Impact | Industry | ||

| Perna viridis is considered to be the second most expensive fouling organism of power plants in Japanese waters, next to Mytilus galloprovincialis, causing major expenses for damage and cleaning (Iwasaki 2006). | |||||

| CAR-III | None | Economic Impact | Fisheries | ||

| Perna viridis is commercially harvested in Venezuela (Segnini de Bravo 2003). | |||||

| CAR-II | None | Economic Impact | Health | ||

| Perna viridis in Kingston Harbor had significant fecal coliform and heavy metal contamination, and will require depuration, if human consumption is going to be encouraged as a form of population control (Buddo et al. 2012). | |||||

| S190 | Indian River | Ecological Impact | Competition | ||

| In experiments in Mosquito Lagoon, Florida, Perna viridis, on fouling plates, reduced the settlement of larvae of Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica), but did not affect the growth of oyster spat (Yuan et al. 2016). | |||||

| G045 | _CDA_G045 (Big Cypress Swamp) | Ecological Impact | Competition | ||

| Year-round high reproductive output and high energy reserves indicate a potential for competition with native Eastern Oysters (Crassostrea virginica (McFarland et al. 2016). | |||||

| S183 | _CDA_S183 (Daytona-St. Augustine) | Ecological Impact | Competition | ||

| Competition between Perna viridis and native bivalves (Crassostrea virginica, Ostrea equestris, Ischadium recurvum, and Geukensia demissa. While these species have different habitat and depth prefernces, there is also considerable overlap (Raabe and Gilg 2020). | |||||

| CAR-VII | Cape Hatteras to Mid-East Florida | Ecological Impact | Competition | ||

| In the Matanzas estuary, Florida, competition between Perna viridis and native bivalves (Crassostrea virginica, Ostrea equestris, Ischadium recurvum, and Geukensia demissa. While these species have different habitat and depth prefernces, there is also considerable overlap (Raabe and Gilg 2020). | |||||

| FL | Florida | Ecological Impact | Competition | ||

| In experiments in Mosquito Lagoon, Florida, Perna viridis, on fouling plates, reduced the settlement of larvae of Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica), but did not affect the growth of oyster spat (Yuan et al. 2016)., 'Green mussels are abundant on oyster reefs in Tampa Bay, and are correlated with high oyster mortalities. On pilings, green mussels displace oysters to a narrow band in the upper intertidal' (Baker et al. 2004). Barber et al. (2005) suggest that P. viridis might be able to out-compete the native Brachidontes exustus (Scorched Mussel) because of the former's faster growth, large size, and greater reproductive output., Competition between Perna viridis and native bivalves (Crassostrea virginica, Ostrea equestris, Ischadium recurvum, and Geukensia demissa. While these species have different habitat and depth prefernces, there is also considerable overlap (Raabe and Gilg 2020)., Year-round high reproductive output and high energy reserves indicate a potential for competition with native Eastern Oysters (Crassostrea virginica (McFarland et al. 2016). | |||||

| FL | Florida | Economic Impact | Shipping/Boating | ||

| Perna viridis fouls US coast Guard buoys, threatening to sink them, and requiring increased cleaning efforts (Baker et al. 2004). | |||||

| FL | Florida | Economic Impact | Fisheries | ||

| Perna viridis is 'abundant on oyster reefs in Tampa Bay, and are correlated with high oyster mortalities' (Baker et al. 2004). | |||||

| FL | Florida | Economic Impact | Industry | ||

| Perna viridis was discovered when it was found to be fouling Tampa Electric Company Gannon Station Power Plant, and several other power plants in Tampa Bay. This mussel increases the cost of fouling control (Baker et al. 2007)., Perna viridis blocked seawater systems in the Mote Marine Laboratory, in Sarasota (Ingrao et al. 2001). | |||||

Regional Distribution Map

Non-native

Native

Cryptogenic

Failed

Occurrence Map

References

Agard, John, Kishore, Rosemarie, Bayne, Brian (1992) Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758): First record of the Indo-Pacific green mussel (Mollusca: Bivalvia) in the Caribbean, Caribbean Marine Studies 3: 59-60Ames, Cheryl and 15 authors (2020) Cassiosomes are stinging-cell structures in the mucus of the upside-down jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana, Communications Biology 3.67: Published onlin

https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-0777-8

Baker, Patrick; Fajans, Jonathan S.; Arnold, William S.; Ingrao, Debra A.; Marelli, Dan C.; Baker, Shirley M. (2007) Range and dispersal of a tropical marine invader, the Asian green mussel, Perna viridis, in subtropical waters of the southeastern United States., Journal of Shellfish Research 26(2): 345-355

Baker, Patrick; Baker, Shirley M.; Fajans, Jon (2004) Nonindigenous marine species in the greater Tampa Bay ecosystem., Tampa Bay Estuary Program, Tampa FL. Pp. <missing location>

Baker, Patrick; Fajans, Jon S.; Baker, Shirly M. (2011) Habitat dominance of a nonindigenous tropical bivalve, Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758), in a subtropical estuary in the Gulf of Mexico, Journal of Molluscan Studies 78: 28-33

Barber, Bruce J.; Fajans, Jonathan S.; Baker, Shirley M.; Baker, Patrick (2005) Gametogenesis in the non-native green mussel, Perna viridis,and the native scorched mussel, Brachidontes exustus, in Tampa Bay, Florida, Journal of Shellfish Research 24(4): 1087-1095

Benson, Amy J.; Marelli, Dan C.; Frischer, Mark E.; Danforth, Jean M.; Williams, James D. (2001) Establishment of the green mussel on the West Coast of Florida., Journal of Shellfish Research 20(1): 21-29

Benson, Amy J./ Fuller, Pam L. & Jacono, Collette C. (2001) Summary report of nonindigenous aquatic speciesin U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service region 4., In: (Eds.) . , Gainesville, FL.. Pp. 1-68

Brinkhurtst, Ralph O. (1989) Varichaetadrilis angustipenis (Brinkhurst and Cook 1966), new combination for Limnodrilus angustipenis (Oligochaeta: Tubificidae), Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 102(2): 311-312

Buddo, Dayne St. A.; Steele, Russell D.; Ranston D'Oyen, Emma (2003) Distribution of the invasive Indo-Pacific green mussel, Perna viridis , in Kingston Harbour, Jamaica., Bulletin of Marine Science 73(2): 433-441

Buddo, Dayne St. A.; Steele, Russell D.; Webber, Mona K. (2012) Public health risks posed by the invasive Indo-Pacific green mussel, Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758) in Kingston Harbour, Jamaica, Bioinvasion Records 1: in press

Chavanich, S.; Tan, L. T.; Vallejo, B.; Viyakarn, V. (2010) Report on the current status of marine non-indigenous species in the Western Pacific region, Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, Subcommission for the Western Pacific, Bangkok, Thailand. Pp. 1-61

Crickenberger, Sam; Sotka, Erik (2009) Temporal shifts of fouling communities in Charleston Harbor, with a report of Perna viridis (Mytilidae), Journal of the North Carolina Academy of Science 125(2): 78-84

Cubillos, V. M.; Ramírez, E. F.; Cruces, E.; Montory, J. A.; .Segura, C. J.; Mardones, D. A. (2018) Temporal changes in environmental conditions of a mid-latitude estuary (southern Chile) and its influences in the cellular response of the euryhaline anemone Anthopleura hermaphroditica, Ecological Indicators 88: 169-180

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.01.015

da Rocha, Rosana M.; Bonnet, Nadia Y. K. (2009) [Ascidians (Tunicata) introduced to the Alactaz archipelago, São Paulo], Iheringia Series Zoologie 99: 27=35

DOI:10.1590/S0073-47212009000100004

de Messano, Luciana Vicente Resende; Gonçalves, José Eduardo Arruda; Messano, Héctor Fabian; Campos, Sávio Henrique Calazans; Coutinho, Ricardo (2022) First report of the Asian green mussel Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: a new record for the southern Atlantic Ocean , BioInvasions records 12(3): : 653–660

Dias, P. Joana; Fotedar, Seema; Gardner, Jonathan P. A.; Snow, Michael (2013) Development of sensitive and specific molecular tools for the efficient detection and discrimination of potentially invasive mussel species of the genus Perna, Management of Biological Invasions 4(2): 155-165

dos Santos, Herick S.; Bertollo, Júlia C.; Creed. Joel C. (2023) Range extension of the Asian green mussel Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758) into a Marine Extractive Reserve in Brazil, BioInvasions Records 12: In press

Edwards, Jennifer (11/16/2011) Cold holds invasive species at bay, St. Augustine Record <missing volume>: published online

Eldredge, L.G. (1994) Perspectives in aquatic exotic species management in the Pacific Islands Vol. I. Introductions of commercially significant aquatic organisms to the Pacific islands, South Pacific Commission. Inshore Fisheries Research Project, Technical Document 7: 1-127

Fell, Paul E. (1974) DIAPAUSE IN THE GEMMULES OF THE MARINE SPONGE. HALICLONA LOOSANOFFI, WITH A NOTE ON THE GEMMULES OF HALICLONA , Biological Bulletin 147: 333-351

Firth, Louise B.; Knights, Antony M.; Bell, Susan S. (2011) Air temperature and winter mortality: Implications for the persistence of the invasive mussel,Perna viridis in the intertidal zone of the south-eastern United States, Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 400: 250-256

GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility) 2017-2023 GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility). https://www.gbif.org/

Gilg, Matthew R. and 5 authors (2010) Recruitment preferences of non-native mussels: Interaction between marine invasions and land-use changes, Journal of Molluscan Studies 76: 333-339

Gilg, Matthew R. and 8 authors (2014) Estimating the dispersal capacity of the introduced green mussel, Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758), from field collections and oceanographic modeling, Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 461: 233-242

Gilg, Matthew R.; Johnson, Eric G.; Gobin, Judith; Bright, B. Matthew; Ortolaza, Alexandra I. (2013) Population genetics of introduced and native populations of the green mussel, Perna viridis: determining patterns of introduction, Biological Invasions 15(2): 459-472

Gracia C. Nelson Rangel-Buitrago, Adriana; (2021) The invasive species Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758 - Bivalvia: Mytilidae) on artificial substrates: A baseline assessment for the Colombian Caribbean Sea, Marine Pollution Bulletin 152(1101927): Published online

Hayes, Keith R.; Cannon, R,; Neil, K.; Inglis, G. (2005) Sensitivity and cost considerations for the detection and eradication of marine pests in ports., Marine Pollution Bulletin 50: 823-834

Hewitt, C. L. (Ed.) (2002) <missing title>, <missing publisher>, <missing place>. Pp. <missing location>

Holland, Brendan (1997) Genetic aspects of a marine invasion, Quarterdeck 5(3): <missing location>

Huang, Zongguo (Ed.), Junda Lin (Translator) (2001) Marine Species and Their Distributions in China's Seas, Krieger, Malabar, FL. Pp. <missing location>

Huhn, Mareike; Nzamani, eviaty P.; Lenz, Mark (2015) A ferry line facilitates dispersal: Asian green mussels Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758) detected in eastern Indonesia, Bioinvasions Records 4: In press

Ingrao, D. A.; Mikkelsen, Paula A.; Hicks, David W. (2001) Another introduced marine mollusk in the Gulf of Mexico, Journal of Shellfish Research 20(1): 13-19

Iwasaki, Keiji (2006) Assessment and Control of Biological Invasion Risks., Shoukadoh Book Sellers,and IUCN, Kyoto and Gland, Switzerland. Pp. 104-112

Lee, Harry 2001-2015 Harry Lee's Florida Mollusca Checklists. <missing URL>

Lee, Jun-Sang; Lee, Yong Seok; Min, Duk-Ki (2010) Introduced molluscan species to Korea, Korean Journal of Malacology Molluscan Research 26(1): 45-49

Lenz, Mark and 11 authors (2011) Non-native marine invertebrates are more tolerant towards environmental stress than taxonomically related native species: Results from a globally replicated study, Environmental Research 111: 943-952

Lomonaco, Cecilia; Santos, Andre S.; Christoffersen, Martin l. (2011) Effects of local hydrodynamic regime on the individual’s size in intertidal Sabellaria (Annelida: Polychaeta: Sabellariidae) and associated fauna at Cabo Branco beach, north-east Brazil, Marine Biodiversity Records 4(e76): Published online

doi:10.1017/S1755267211000807;

Lopeztegui-Castillo, Alexander and 5 authors (2014) Spatial and temporal patterns of the nonnative green mussel Perna viridis in Cienfuegos Bay, Cuba, Journal of Shellfish Research 33(1): 273-278

Lutaenko, Konstantin A.; Furota,Toshio; Nakayama, Satoko; Shin, Kyoungsoon; Xu, Jing (2013) <missing title>, Northwest Pacific Action Plan- Data and Information Network Regional Activity Center, Beijing, China. Pp. <missing location>

Manoj Nair, R.;Appukuttan, K. K. (2003) Effect of temperature on the development, growth, survival and settlement of green mussel Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758), Aquaculture Research 34: 1037-1045

McDonald, Justin I. (2012) Detection of the tropical mussel species Perna viridis in temperate Western Australia: possible association between spawning and a marine heat pulse, Aquatic Invasions 7: in press

McFarland, Katherine; Baker, Shirley; Baker, Patrick; Rybovich, Molly; Volety, Aswani K. (2015) Temperature, salinity, and aerial exposure tolerance of the invasive mussel, Perna viridis, in estuarine habitats: implications for spread and competition with native oysters, Crassostrea virginica, Estuaries and Coasts 38: 1619-1628

McFarland, Katherine; Soudant, Philippe; Jean, Fred; Volety, Aswani K. (2016) Reproductive strategy of the invasive green mussel may result in increased competition with native fauna in the southeastern United States, Aquatic Invasions 11: In press

Mead, A.; Carlton, J. T.; Griffiths, C. L.; Rius, M. (2011a) Revealing the scale of marine bioinvasions in developing regions: a South African re-assessment, Biological Invasions 13(9): 1991-2008

Mitchem, E. L.; Fajans, J. M.; Baker, S. M. (2007) Contrasting responses of two native crustaceans to non-indigenous prey, the green mussel Perna viridis, Florida Scientist 70(2): 180-188

Okey, Thomas. A. ; Shepherd, Scoresby. A.; Martínez, Priscilla C. (2003) A new record of anemone barrens in the Galápagos, Noticias de Galapagos 62: 17-20

Pérez, Julio E.; Alfonsi, Carmen; Salazar, Sinatra K.; Macsotay, Oliver Barrios, Jorge; Escarbassiere, Rafael Martinez (2007) Especies marinas exóticas y criptogénicas en las costas de Venezuela., Boletino del Instituto Oceanographico de Venezuela 46(1): 79-96

Perry, Harriet; Yeager, David (2006) <missing title>, Gulf Coast Research Laboratory- University of Southern Mississiuppi, Ocean Springs MS. Pp. 8

Piola, Richard F.; McDonald, Justin I. (2012) Marine biosecurity: The importance of awareness, support and cooperation in managing a successful incursion response, Marine Pollution Bulletin 64: 1766-1773

Power, Alan J.; Walker, Randal L.; Payne, Karen; Hurley, Dorset (2004) First occurrence of the nonindigenous green mussel, Perna viridis in coastal Georgia, Journal of Shellfish Research 23: 741-744

Rajagopal, S.; Venugoplan, V. G.; Van der Velde, G. Jenner, H. A. (2006) Greening of the coasts: a review of the Perna viridis success story., Aquatic Ecology 40: 273-297

Rajagopal, S.;Nair, K.V.K.; Van Der Velde, G.; Jenner, H.A. (1997) Seasonal settlement and succession of fouling communities in Kalpakkam, east coast of India., Netherlands Journal of Aquatic Ecology 30(4): 309-325

Ruiz, Gregory M.; Geller, Jonathan (2018) Spatial and temporal analysis of marine invasions in California, Part II: Humboldt Bay, Marina del Re, Port Hueneme, and San Francisco Bay, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center & Moss Landing Laboratories, Edgewater MD, Moss Landing CA. Pp. <missing location>

Segnini de Bravo, M.; Chung, K. S.; Perez, J. E. (1998) Salinity and temperature tolerances of the green and brown mussels, Perna viridis and Perna perna (Bivalvia: Mytilidae), Revista de Biologia Tropical 46(Suppl. 5): 121-125

Segnini de Bravo, Mary Isabel (2003) Influence of salinity on the physiological conditions in mussels, Perna perna and Perna viridis (Bivalvia: Mytilidae), Revista de Biologia Tropical 51(Suppl. 4): 153-158

Sheehy, Daniel J.; Vik, Susan F. (2009) The role of constructed reefs in non-indigenous species introductions and range expansions, Ecological Engineering 36: 1-1

Siddall, Scott E. (1980) A clarification of the genus Perna (Mytilidae)., Bulletin of Marine Science 30(4): 858-870

Siegert, Nathan W. McCullough, Deborah G. Liebhold, Andrew M. Telewski, Frank W. (2014) Dendrochronological reconstruction of the epicentre and early spread of emerald ash borer in North America, Diversity and Distributions 20: 847–858

Soares, Marcelo Oliveira; Xavier, Rafael de Lima, Francisco; Nalu Maia Dias, Monteiro da Silva, Maiara Queiroz; Pinto; de Lima Jadson; Xerez Barroso (2022) Alien hotspot: Benthic marine species introduced in the Brazilian semiarid coast, Marine Pollution Bulletin 174(113250): Published online

Spinuzzi, Samantha and 5 authors (2012) <missing title>, University of Central Florida, Orlando FL. Pp. unpaged

Stafford, Heath; Willan, Richard C. (2007a) <missing title>, state of Queensland, Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries, Cairns. Pp. <missing location>

Stafford, Heath; Willan, Richard C.; Neil, Kerry M. (2007b) The Asian Green Mussel, Perna viridis, breeds in Trinity Inlet, tropical northern Australia, Molluscan Research Molluscan Research 27(2): 105-109

Tavares, M. R.; .Franco, A. C. S. ; . Ventura, C. R. R.; .Santos, L. N. (2021) Geographic distribution of Ophiothela brittle stars (Echinodermata: Ophiuroidea): substrate use plasticity and implications for the silent invasion of O. mirabilis in the Atlantic, Hydrobiologia 848: 2093-2103

Ueda, Ikuo (2000) Distribution of the green mussel, Perna viridis, along the coast of Sagami Bay, Journal of the Japanese Association of Zoological Gardens and Aquariums 41(2): 54-60

Uemori, Tatsushi; Horikoshi, Masuoki (1991) Death and survival during winter season in different populations of the green mussel, Perna viridis (Linnaeus), living in different sites within a cove on the western coast of Tokyo Bay., La Mer 29: 103-107

Urian, Alyson G.; Hatle, John D.; Gilg, Matthew R. (2010) Thermal constraints for range expansion of the invasive green mussel, Perna viridis, in the southeastern United States, Journal of Experimental Zoology 315: 12-21

USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2003-2024 Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database. https://nas.er.usgs.gov/

Uttieri, Marco and 24 authors (2023) The Distribution of Pseudodiaptomus marinus in European and Neighbouring Waters—A Rolling Review, Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 11(1238): Published online

https://doi.org/10.3390 /jmse11061238

Wood, Ann R.; Apte, Smita; MacAvoy, Elizabeth S.; Gardner, Jonathan P.A. (2007) A molecular phylogeny of the marine mussel genus Perna (Bivalvia: Mytilidae) based on nuclear (ITS1&2) and mitochondrial (COI) DNA sequences, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 44: 685-698

Yang,Yi; Abalde, Samuel; Carlos; Afonso L. M., Tenorio, Manuel J.; Puillandre, Nicolas; Templado, José; Zardoya, Rafael (2021) Mitogenomic phylogeny of mud snails of the mostly Atlantic/ Mediterranean genus Tritia (Gastropoda: Nassariidae), Zoologica Scripta Published online: <missing location>

Yuan, W. Samantha; Hoffman, Eric A.; Walters, Linda J. (2016) <missing title>, 18 <missing publisher>, <missing place>. Pp. 689-701