Invasion History

First Non-native North American Tidal Record: 1953First Non-native West Coast Tidal Record: 1961

First Non-native East/Gulf Coast Tidal Record: 1953

General Invasion History:

Threadfin Shad (Dorosoma petenense) is native to the Mississippi and Gulf of Mexico drainages from Indiana and Illinois south to Guatemala (Page and Burr 1991). It may have been introduced to Gulf drainages east of the Mississippi River, and to the Florida peninsula in the first half of the 20th century (Fuller et al. 1999; USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2018). However, there is a museum specimens from the St. Johns River collected before 1877 (Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 2018). They were widely introduced as a forage fish to reservoirs in North America starting in 1950's (Carlander 1969). This was mainly due to the perceived need for a small, planktivorous prey fish to support stocked game fish in reservoirs, and some trial-and-error in matching prey and predators (Courtenay and Moyle 1989). They rapidly colonized estuaries in the southeastern US and the San Francisco Bay area, occasionally entering marine waters (Robins et al. 1986; Cohen and Carlton 1995; Dill and Cordone 1997). Tendencies for winter die-offs, 'boom and bust' population fluctuations, and unpredictable invasiveness has led to a decline in introductions in recent years (Courtenay and Moyle 1989; Jenkins and Burkhead 1993; Fuller et al. 1999). However, the range of threadfin shad on the US East Coast has been creeping northward and were discovered in the upper Delaware Bay estuary in 2022 and 2023 (Keller et al. 2024).

North American Invasion History:

Invasion History on the West Coast:

In 1955 Threadfin Shad were stocked into Lake Havasu, Arizona. From there, the fish spread throughout the lower Colorado to River to the Mexican border. In 1959, they were introduced to reservoirs in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River system and reached the Delta and San Francisco Bay by 1961 (Cohen and Carlton 1995; Dill and Cordone 1997). By 1967, Threadfin Shad had become one of the most abundant fishes in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (Dill and Cordone 1997). They have occasionally been captured in marine waters of the San Francisco Bay and adjacent coast, as far north as Yaquina Bay Oregon, and south of Long Beach (Miller 1972; Krygier et al. 1973; Lee et al. 1980; Eschmeyer et al. 1983). Additional reports have come from tributaries of Monterey Bay (Elkhorn Slough, Salinas and Pajoro Rivers) and from the Santa Clara River in Ventura County (Kukowski 1972; Yoakavich et al. 1991; USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2018), so it is possible that additional California rivers have been colonized.

Their population has gone through a series of peaks and crashes in the last 40 years, and dropped sharply after 2002, reaching a record low in 2012 (Feyrer et al. 2009; Latour et al. 2016). The decline of threadfin shad has been treated as part of the general phenomenon termed 'Pelagic Organism Decline', due in part to watershed modifications and the removal of phytoplankton by the invasive Asian Brackishwater Clam (Corbula amurensis) (Sommer et al. 2007; Mac Nally et al. 2010; Thomson et al. 2010). However, in a 2014 survey in the Delta, Threadfin Shad and Mississippi Silverside (Menidia audens together constituted 43% of the nekton biomass (Feyrer et al. 2016).

Invasion History on the East Coast:

Threadfin Shad was collected in the St. Johns River before 1877 and again in the 1940s, so it may be native in that system (Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 2018; USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2018). Introductions were made in the 1950s in the Altamaha River (Georgia), the Roanoke River and Back Bay-Currituck Sound (Virginia-North Carolina), the Potomac River probably in many other southeastern Atlantic states. Threadfin Shad were found in coastal waters in Georgia as early as the 1950s, and by the 1970s had been found in coastal and estuarine waters from Maryland to Florida (Lee et al. 1980; Lee et al. 1981; Jenkins and Burkhead 1993; USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2018). They’ve also been caught in upper Chesapeake Bay, in the Rhode River and Aberdeen (Lee et 1980; Rob Aguilar, personal communication 2012). In 2022 and 2023 threadfin shad were caught during electrofishing sampling in the upper Delaware Bay estuary (Keller et al. 2024). This fish is likely to expand its range with climate change.

Invasion History in Hawaii:

One source reports introductions of Threadfin Shad to the Hawaiian Islands in 1905 (Devick 1991, cited by USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2018), but other authors give the date as 1958 (Maciolek 1984; Randall 1987). It has become well-established in freshwater reservoirs on Oahu, Kauai, and Maui, but does not seem to have entered estuaries or marine habitats. In the Hawaiian Islands where they were established, an attempt was made in the 1960s-70s to acclimate large numbers of Threadfin shad to salt-water ponds so that they could be used as bait for the Skipjack Tuna (Euthynnus pelamis) fishery. This was unsuccessful, because this herring species did not tolerate the extensive handling involved in use as bait (Randall 1987).

Invasion History Elsewhere in the World:

Threadfin Shad were introduced as forage fish to reservoirs in Puerto Rico in 1963, and now are found in many reservoirs on the island (USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2018).

Description

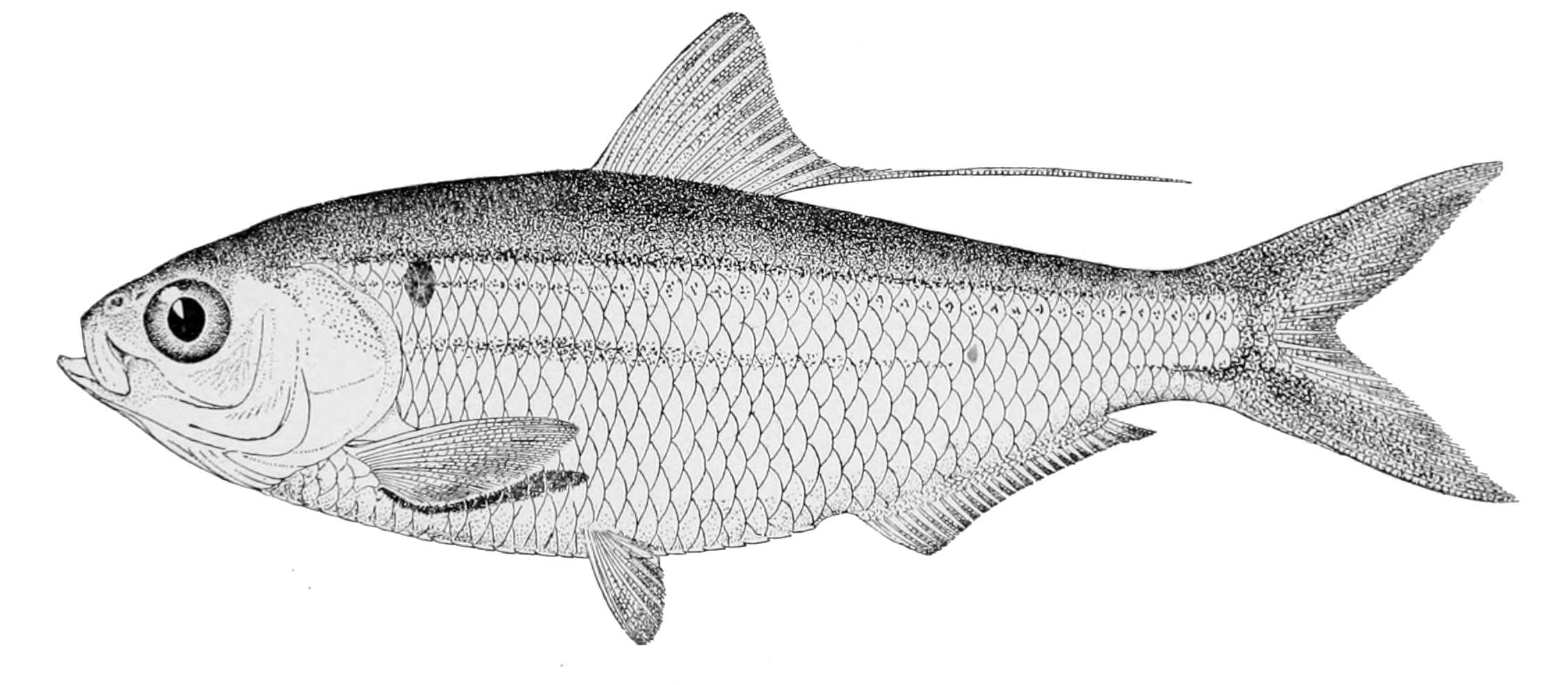

Threadfin Shad (Dorosoma petenense) is a fish of the herring family (Clupeidae), predominantly occurring in freshwater, but also entering estuarine and marine waters. Its body is streamlined, but deep and laterally compressed. There is a single soft-rayed dorsal fin, with the last ray prolonged into a long filament, a soft-rayed anal fin, and the pelvic fins are abdominal. There are 11-14 dorsal rays, and 17-27 anal rays. The tail is deeply forked. The scales are large and easily loosened. The belly is keeled with 14-15 prominent bony scutes. Adult fish can reach 230 mm. The body is dark greenish or bluish dorsally, and bright silver on the sides, with a dark spot on the rear of the gill cover, and one or two rows of dusky lateral stripe below it (Miller1972; Eschmeyer and Herald 1983; Robins et al. 1986; Murdy et al. 1997).

Jones et al. (1978) and Wang (1985) describe developmental stages.

Taxonomy

Taxonomic Tree

| Kingdom: | Animalia | |

| Phylum: | Chordata | |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata | |

| Superclass: | Osteichthyes | |

| Class: | Actinopterygii | |

| Subclass: | Neopterygii | |

| Infraclass: | Teleostei | |

| Superorder: | Clupeomorpha | |

| Order: | Clupeiformes | |

| Suborder: | Clupeoidei | |

| Family: | Clupeidae | |

| SubFamily: | Dorosomatinae | |

| Genus: | Dorosoma | |

| Species: | petenense |

Synonyms

Meletta petenensis (Günther, 1867)

Signalosa atchafalayae (Evermann & Kendall, 1898)

Signalosa atchafalayae campi (Weed, 1925)

Signalosa atchafalayae vanhyningi (Weed, 1925)

Signalosa petenense (None, None)

Potentially Misidentified Species

Dorosoma cepedianum (Gizzard Shad) is a predominantly freshwater species, also entering seawater. It is native from southern New England, the Great Lakes, and the upper Mississippi and Missouri basins to the Gulf. Gizzard Shad are larger (to 550 mm) than Threadfin Shad and deeper-bodied (Page and Burr 1991; Murdy et al. 1997).

Opisthonema medirostrum

Opisthonema oglinum (Middling Thread Herring) is strictly marine, and quite similar to Threadfin Shad, with a filamentous last dorsal ray, but lacking a spot behind the gill cover. It ranges from southern California to Peru (Miller 1972).

Opisthonema oglinum

Opisthonema oglinum (Atlantic Thread Herring) is strictly marine, and quite similar, with a filamentous last dorsal ray, but with a larger dark spot behind the gill cover and 6-7 lateral stripes (Robins et al. 1986).

Ecology

General:

Threadfin Shad (Dorosoma petenense) is primarily a freshwater resident, with most populations occurring in freshwater, but adults frequently disperse through estuaries and marine waters (Jones et al. 1978; Page and Burr 1991; Fuller et al. 1999). Sexes are separate. Adults mature in 1-3 years at 49-55 mm. Female fecundity ranges from 800-21,000 eggs, increasing with size. Spawning occurs twice a year, in spring and fall, at temperatures of 14 to 27 C. In the San Francisco Bay Delta, spawning occurs mostly in April and May (Wang 1986). Spawning occurs at night in fresh or 'almost fresh water', in open water, or over vegetation and coarse wood debris (Jones et al. 1978). Eggs sink and adhere to vegetation, rocks, and sticks (Wang 1986). Eggs hatch in 3 days at 27 C, or longer at lower temperatures (Jones et a1. 1978). The newly hatched yolk-sac larva is ~5 mm long and strongly elongated. The larvae are planktonic. By the time the fish reaches 25 mm, it is a juvenile approaching the adult body shape (Wang 1986).

Threadfin Shad have many landlocked populations, but they are highly mobile, dispersing along rivers, entering estuaries, and dispersing along coastlines. However, they require fresh water for spawning and early development (Jones et al. 1978; Dill and Cordone 1997). Juveniles often move into brackish water, up to 15.5 PSU, but are most common in fresh and lower-salinity water. Adults have been collected at salinities of 32 PSU, probably higher (Jones et al. 1976). As a species with a warm-temperate subtropical range, populations at the northern edge of its range in reservoirs are often subject to diebacks, as in Virginia reservoirs, and the San Francisco estuary (Jenkins and Burkhead 1993; Dill and Cordone 1997). River and coastal populations can avoid low temperatures by migration. Threadfin Shad are pelagic fish, usually moving in large schools. They are planktivorous, filter-feeding on phytoplankton, copepods, and plant detritus (Murdy et al. 1997; Feyrer et al. 2003; Froese and Pauly 2018). As a small fish, low in the food chain, they have a wide range of predators. In the San Francisco estuary delta, Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis), is the major predator, but Threadifn Shad are also eaten by Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) and the native Sacramento Pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus grandis) (Nobriga and Feyrer 2007). Likely predators in Atlantic estuaries include Striped Bass (native), Largemouth Bass and introduced Blue Catfish.

Food:

Phytoplankton, Zooplankton, Detritus

Consumers:

Predatory fishes

Trophic Status:

Suspension Feeder

SusFedHabitats

| General Habitat | Fresh (nontidal) Marsh | None |

| General Habitat | Grass Bed | None |

| General Habitat | Nontidal Freshwater | None |

| General Habitat | Tidal Fresh Marsh | None |

| General Habitat | Unstructured Bottom | None |

| General Habitat | Salt-brackish marsh | None |

| Tidal Range | Subtidal | None |

| Vertical Habitat | Nektonic | None |

Life History

Tolerances and Life History Parameters

| Minimum Temperature (ºC) | 5 | Field Data- Winter die-offs have been reported at temperatures of 1-7 C (Jones et al. 1978). |

| Maximum Temperature (ºC) | 34.9 | Field Data- (Jones et al. 1978) |

| Minimum Salinity (‰) | 0 | Field Data- (Jones et al. 1978) |

| Maximum Salinity (‰) | 32.3 | Field Data- (Jones et al. 1978) |

| Minimum Reproductive Temperature | 14.4 | Field Data- (Jones et al. 1978) |

| Maximum Reproductive Temperature | 27.2 | Field Data- (Jones et al. 1978) |

| Minimum Reproductive Salinity | 0 | Field Data- (Jones et al. 1978) |

| Maximum Reproductive Salinity | 1 | Field Data- (Jones et al. 1978) |

| Minimum Length (mm) | 52 | Jones et al. 1978 |

| Maximum Length (mm) | 220 | but more usually 100 mm (Robins et al. 1986; Froese and Pauly 2018) |

General Impacts

Threadfin Shad (Dorosoma petenense) has been widely stocked as a forage fish, because of its small size and planktivorous, pelagic habits, making it a potential prey for popular game fishes. Threadfin Shad have been considered a successful introduction overall, but negative impacts include their unexpected ability to disperse over long distances and colonize new habitats, tendency for dramatic population fluctuations, die-offs due to cold weather, and competition with larval and juvenile, gamefish and endangered species (Courtenay and Moyle 1989; Crowl and Boxrucker 1988; Guest et al. 1990; Dill and Cordone 1997). After its introduction to reservoirs in the Sacramento-San Joaquin watershed in 1959, Threadfin Shad colonized the San Francisco Bay estuary, becoming the most abundant fish in the system by 1967 (Feyrer et al. 2009). Impacts of Threadfin Shad on Atlantic Coast estuaries have not been well-studied, but statistical analyses indicate that they affect the abundance of native clupeids in Chesapeake Bay tidal rivers (Herbert Austin, pers. comm. 1998).

Economic Impacts

Fisheries- Threadfin Shad was widely stocked in reservoirs throughout the southern and central US in the 1950s, as a prey species to support stocked populations of popular game fishes such as such as Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides), Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis), Crappies (Pomoxis spp.), and Striped Bass-White Bass hybrids (Morone saxatilis X chrysops). In the San Francisco estuary, it became important as the primary prey of the Striped Bass, the system's major gamefish (Feyrer et al. 2009). The introductions were generally considered successful, but some problems were noted. Rapidly growing populations of Threadfin Shad could outrun their predators, and the dense populations of this planktivorous fish could out-compete the larvae and juveniles of the gamefish (Crowl and Boxrucker 1988; Guest et al. 1990; Hirst and DeVries 1994). In addition, Threadfin Shad turned out to be unexpectedly mobile, colonizing rivers, reservoirs, and estuaries far beyond their intended range (Dill and Cordone 1997). This fish was also sensitive to low winter temperatures, and suffered diebacks and extinctions in Virginia, North Carolina, and other borderline southern states (Jenkins and Burkhead 1994; Fuller et al. 1999).

Ecological Impacts

Competition- Threadfin Shad (Dorosoma petenense) is a pelagic, planktivorous fish, feeding on phytoplankton, cladocerans and copepods. As such, it is a potential competitor with native, small, planktivorous fishes, and the larvae and juveniles of larger fishes. In the San Francisco estuary, its diet overlaps with the endangered native endemic Delta Smelt (Hypomesus transpacifius), whose population is declining. Both species feed largely on planktonic copepods (Feyrer et al. 2003). Shad can also adversely affect sportfish recruitment by altering the abundance and size structure of zooplankton, reducing food availability. Threadfin Shad adversely affected the recruitment of White Crappie (Pomoxis annularis) in Oklahoma reservoirs, but similar effects on juveniles of other sport fishes and adults of planktivores such as Bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus) are quite likely (Crowl and Boxrucker 1988; Guest et al. 1990). Possible competition between larvae of D. petenense and Micropterus spp. (M. salmoides, Largemouth Bass, and M. punctulatus, Spotted Bass) was studied in two Alabama reservoirs. Some diet overlap between bass and shad larvae was found, but was judged to be insignificant, given bass' preference for larger prey, and the high zooplankton abundances during the larval period (Hirst and DeVries 1994).

Food/Prey- Threadfin Shad was widely stocked as a forage fish because of its small size, planktonic feeding, and rapid reproduction (Courtenay and Moyle 1989; Dill and Cordone 1997). In different reservoirs, it was stocked as food for Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides), Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis), Crappies (Pomoxis spp., and Striped Bass-White Bass hybrids (Morone saxatilis X chrysops) (Crowl and Boxrucker 1988; Guest et al. 1990; Hirst and DeVries 1994). In the San Francisco estuary, the major predators of Threadfin Shad were the native Sacramento Pike Minnow (Ptychocheilus grandis) and the introduced Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis) and Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) (Nobriga and Feyrer 2007; Nobriga and Feyrer 2008; Feyrer et al. 2009). In Atlantic estuaries, Striped Bass and Largemouth Bass are likely predators of Threadfin Shad.

Regional Impacts

| NEP-V | Northern California to Mid Channel Islands | Ecological Impact | Competition | ||

| Threadfin Shad in the San Francisco Bay Delta showed a close dietary overlap (primarily planktonic copepods) with the endangered Delta Smelt (Hypomesus transpacifricus (Feyerer et al. 2003). | |||||

| NEP-V | Northern California to Mid Channel Islands | Ecological Impact | Food/Prey | ||

| Threadfin Shad in the San Francisco Bay Delta were a major prey item for Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis), Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) and Sacramento Pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus grandis) (Nobriga and Feyrer 2007; Nobriga and Feyrer 2008; Feyrer et al. 2009) | |||||

| P090 | San Francisco Bay | Ecological Impact | Competition | ||

| Threadfin Shad in the San Francisco Bay Delta showed a close dietary overlap (primarily planktonic copepods) with the endangered Delta Smelt (Hypomesus transpacifricus (Feyrer et al. 2003). | |||||

| P090 | San Francisco Bay | Ecological Impact | Food/Prey | ||

| Threadfin Shad in the San Francisco Bay Delta were a major prey item for Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis), Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) and Sacramento Pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus grandis) (Nobriga and Feyrer 2007; Nobriga and Feyrer 2008; Feyrer et al. 2009) | |||||

| P090 | San Francisco Bay | Economic Impact | Fisheries | ||

| Threadfin Shad were stocked in the San Francisco Bay Delta as a forage fish for introduced gamefish, especially Striped and Largemouth Bass. Although it has undergone recent declines, it still supports major sport fisheries for Striped Bass and Largemouth Bass (Dill and Codone 1997; Feyrer et al. 2009). | |||||

| NEP-V | Northern California to Mid Channel Islands | Economic Impact | Fisheries | ||

| Threadfin Shad were stocked in the San Francisco Bay Delta watershed as a forage fish for introduced gamefish, especially Striped and Largemouth Bass. Although it has undergone recent declines, it still supports major sport fisheries for Striped Bass and Largemouth Bass (Dill and Codone 2007; Feyrer et al. 2009). | |||||

| CA | California | Ecological Impact | Competition | ||

| Threadfin Shad in the San Francisco Bay Delta showed a close dietary overlap (primarily planktonic copepods) with the endangered Delta Smelt (Hypomesus transpacifricus (Feyerer et al. 2003)., Threadfin Shad in the San Francisco Bay Delta showed a close dietary overlap (primarily planktonic copepods) with the endangered Delta Smelt (Hypomesus transpacifricus (Feyrer et al. 2003). | |||||

| CA | California | Ecological Impact | Food/Prey | ||

| Threadfin Shad in the San Francisco Bay Delta were a major prey item for Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis), Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) and Sacramento Pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus grandis) (Nobriga and Feyrer 2007; Nobriga and Feyrer 2008; Feyrer et al. 2009), Threadfin Shad in the San Francisco Bay Delta were a major prey item for Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis), Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) and Sacramento Pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus grandis) (Nobriga and Feyrer 2007; Nobriga and Feyrer 2008; Feyrer et al. 2009) | |||||

| CA | California | Economic Impact | Fisheries | ||

| Threadfin Shad were stocked in the San Francisco Bay Delta watershed as a forage fish for introduced gamefish, especially Striped and Largemouth Bass. Although it has undergone recent declines, it still supports major sport fisheries for Striped Bass and Largemouth Bass (Dill and Codone 2007; Feyrer et al. 2009)., Threadfin Shad were stocked in the San Francisco Bay Delta as a forage fish for introduced gamefish, especially Striped and Largemouth Bass. Although it has undergone recent declines, it still supports major sport fisheries for Striped Bass and Largemouth Bass (Dill and Codone 1997; Feyrer et al. 2009). | |||||

Regional Distribution Map

Non-native

Native

Cryptogenic

Failed

| Bioregion | Region Name | Year | Invasion Status | Population Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR-I | Northern Yucatan, Gulf of Mexico, Florida Straits, to Middle Eastern Florida | 0 | Native | Established |

| CAR-VII | Cape Hatteras to Mid-East Florida | 1953 | Non-native | Established |

| NEP-V | Northern California to Mid Channel Islands | 1961 | Non-native | Established |

| NEP-IV | Puget Sound to Northern California | 1970 | Non-native | Unknown |

| NEP-VI | Pt. Conception to Southern Baja California | 1970 | Non-native | Unknown |

| NA-ET3 | Cape Cod to Cape Hatteras | 1953 | Non-native | Established |

| S180 | St. Johns River | 1877 | Crypogenic | Established |

| G070 | Tampa Bay | 1963 | Crypogenic | Established |

| P050 | San Pedro Bay | 1962 | Non-native | Unknown |

| M130 | Chesapeake Bay | 1953 | Non-native | Established |

| S190 | Indian River | 1954 | Crypogenic | Established |

| S010 | Albemarle Sound | 1953 | Non-native | Established |

| S020 | Pamlico Sound | 1991 | Non-native | Established |

| S050 | Cape Fear River | 0 | Non-native | Established |

| S056 | _CDA_S056 (Northeast Cape Fear) | 1974 | Non-native | Established |

| S060 | Winyah Bay | 1974 | Non-native | Established |

| S070 | North/South Santee Rivers | 1974 | Non-native | Established |

| S076 | _CDA_S076 (South Carolina Coastal) | 1974 | Non-native | Established |

| S080 | Charleston Harbor | 1974 | Non-native | Established |

| S090 | Stono/North Edisto Rivers | 1974 | Non-native | Established |

| S100 | St. Helena Sound | 1974 | Non-native | Established |

| S110 | Broad River | 1974 | Non-native | Established |

| S120 | Savannah River | 1968 | Non-native | Established |

| S130 | Ossabaw Sound | 1961 | Non-native | Established |

| S140 | St. Catherines/Sapelo Sounds | 1961 | Non-native | Established |

| S125 | _CDA_S125 (Ogeechee Coastal) | 1961 | Non-native | Established |

| G045 | _CDA_G045 (Big Cypress Swamp) | 1952 | Crypogenic | Established |

| G050 | Charlotte Harbor | 0 | Crypogenic | Established |

| S196 | _CDA_S196 (Cape Canaveral) | 0 | Crypogenic | Established |

| S175 | _CDA_S175 (Nassau) | 1976 | Non-native | Established |

| G074 | _CDA_G074 (Crystal-Pithlachascotee) | 0 | Crypogenic | Established |

| S200 | Biscayne Bay | 1987 | Crypogenic | Established |

| G100 | Apalachicola Bay | 1950 | Crypogenic | Established |

| G120 | Choctawhatchee Bay | 0 | Crypogenic | Established |

| G130 | Pensacola Bay | 1959 | Crypogenic | Established |

| G150 | Mobile Bay | 0 | Crypogenic | Established |

| G240 | Calcasieu Lake | 0 | Native | Established |

| G220 | Atchafalaya/Vermilion Bays | 0 | Native | Established |

| G250 | Sabine Lake | 0 | Native | Established |

| G260 | Galveston Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| G300 | Aransas Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| G330 | Lower Laguna Madre | 0 | Native | Established |

| G170 | West Mississippi Sound | 0 | Native | Established |

| CAR-II | None | 0 | Native | Established |

| P080 | Monterey Bay | 1972 | Non-native | Established |

| P090 | San Francisco Bay | 1961 | Non-native | Established |

| P100 | Drakes Estero | 0 | Non-native | Unknown |

| P130 | Humboldt Bay | 1970 | Non-native | Unknown |

| P210 | Yaquina Bay | 1972 | Non-native | Unknown |

| GL-I | Lakes Huron, Superior and Michigan | 2018 | Non-native | Unknown |

| M090 | Delaware Bay | 2022 | Non-native | Established |

Occurrence Map

| OCC_ID | Author | Year | Date | Locality | Status | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|

References

Keller D, Morrill D, Rohrback C (2024) First records of threadfin shad (Dorosoma petenense Günther, 1867) in the upper Delaware River estuary indicate northward range expansion, Bioinvasion Records 13(2): 551–556Precht, William F. Hickerson, Emma L.; Schmah, George P.; Aronson, Richard B. (2014) The invasive coral Tubastraea coccinea (Lesson, 1829): Implications for natural habitats in the Gulf of Mexico and the Florida Keys, Gulf of Mexico Science 2014: 55-59

Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 1998 Ichthyological Collection Catalog. <missing URL>

Alvarez-Aguilar, A.; Van Rensburg, H.; Simon, C. A. (2022) Impacts of alien polychaete species in marine ecosystems: a systematic review, Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0025315422000315: Published online

https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0025315422000315

Cacabelos, Eva; IGestoso, Ignacio; Ramalhosa , Patrício; Canning?Clode, João (2022) Role of non?indigenous species in structuring benthic communities after fragmentation events: an experimental approach, Biological Invasions Published online: Published online

Carlander, Kenneth D. (1969) Handbook of freshwater fishery biology. Vol. 1., In: (Eds.) . , Ames. Pp. <missing location>

Chesapeake Bay Program (2007) A Comprehensive List of Chesapeake Bay Basin Species , Chesapeake Bay Program, Annapolis MD. Pp. <missing location>

Cohen, Andrew N.; Carlton, James T. (1995) Nonindigenous aquatic species in a United States estuary: a case study of the biological invasions of the San Francisco Bay and Delta, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Sea Grant College Program (Connecticut Sea Grant), Washington DC, Silver Spring MD.. Pp. <missing location>

Courtenay, Walter R., C. Richard Robins (1989) Fish introductions: Good management, mismanagement, or no management, Reviews in Aquatic Sciences 1(157-172): <missing location>

Dahlberg, Michael D., Scott, Donald C. (1971) Introductions of freshwater fishes in Georgia, Bulletin of the Georgia Academy of Science 29(245-252): <missing location>

Dauvin, Jean-Claude; Dewarumrez, Jean-Marie; Gentil, Franck (2003) [Updated list of polychaete annelids reported in the English Channel], Cahiers de Biologie Marine 44: 67-95

Dauvin, Jean-Claude; Dewarumrez, Jean-Marie; Gentil, Franck (2003) [Updated list of polychaete annelids reported in the English Channel], Cahiers de Biologie Marine 44: 67-95

Dill, William A.; Cordone, Almo J. (1997) History and status of introduced fishes in California, 1871-1996, California Department of Fish and Game Fish Bulletin 178: 1-414

Eschmeyer, William N.; Herald, Earl S.; Hamman, Howard (1983) A field guide to Pacific coast fishes: North America, Houghton Mifflin, Boston. Pp. <missing location>

Feyrer, Frederick; Herbold, Bruce; Matern, Scott A.; Moyle, Peter (2003) Dietary shifts in a stressed fish assemblage: consequences of a bivalve invasion in the San Francisco estuary., Environmental Biology of Fishes 67: 277-288

Feyrer, Frederick; Sommer, Ted; Slater, Steven B. (2009) Old school vs. new school: status of threadfin shad (Dorosoma petenense) five decades after its introduction to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science 7(1): published online

Finucane, John H. (1965) Threadfin Shad in Tampa Bay, Florida, Quarterly Journal of Academy of Sciences 28: 267-270

Fuller, P.M., Nico, L.G., Williams, J.D. (1999) Nonindigenous fishes introduced into inland waters of the United States, American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, MD. Pp. <missing location>

Fuller, Pam. L.; Nico, Leo; Williams, J. D. (1999) Nonindigenous fishes introduced into inland waters of the United States, American Fisheries Society, Bethesda MD. Pp. <missing location>

Gotshall, D.,Allen, G., Barnhart, R.A. (1980) An annotated checklist of fishes from Humboldt Bay, california, California Fish and Game 66(4): 230-232

Grimaldo, Lenny F.; Miller, Robert E.; Peregrin, Christopher M.; Hymanson, Zachary (2003) Early life history of fishes in the San Francisco estuary and watershed., American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland. Pp. 81-96

Grimaldo, Lenny; Miller, Robert E.; Hymanson, ZacharyPeregrin, Chris M., (2012) Fish assemblages in reference and restored tidal freshwater marshes of the San Francisco estuary, San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science 10(1): https://doi.org/10.1

Guest, W. Clell; Drenner, Ray W.; Threlkeld, Steven T., Martin, F. Douglas; Smith, J. Durward (1990) Effects of gizzard shad and threadfin shad on zooplankton and young-of-year white crappie production, Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 119(3): 529-536

Haramis, G. Michael; Kearns, Gregory D. (2007) Herbivory by resident geese: the loss and recovery of wild rice along the tidal Patuxent River, Journal of Wildlife Management 71(3): 788-794

Hirst, Shawn C.; DeVries, Dennis R. (1994) Assessing the potential for direct feeding interactions among larval black bass and larval shad in ten southeastern reservoirs., Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 123: 173-181

Jackson, James R.; Bryant, Shari (1993) Impacts of a threadfin shad winterkill on black crappie in a North Carolina reservoir, Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Southeast Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies 47: 511-519

Jenkins, Robert E.; Burkhead, Noel M. (1993) Freshwater Fishes of Virginia, American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, MD. Pp. <missing location>

Jones, Philip W.; Martin, F. Douglas; Hardy, Jerry D., Jr. (1978) Development of fishes of the mid-Atlantic Bight. V. 1. Acipenseridae through Ictaluridae., In: (Eds.) . , Washington DC. Pp. <missing location>

Kajihara, Hiroshi; Sun, Shi-Chun; , Chernyshev, Alexei V.; Chen, Hai-Xia; Ito, Katsutoshi; Asakawa, Manabu; Maslakova, Svetlana A.;Norenburg; Jon L. Strand, Malin; Sundberg, Per: Iwata, Fumio (2013) Taxonomic Identity of a Tetrodotoxin-Accumulating Ribbon-worm Cephalothrix simula (Nemertea: Palaeonemertea): A Species Artificially Introduced from the Pacific to Europe, Zoological Science 30(11): 985-997

doi:10.2108/zsj.30.985

Krygier, Earl E.; Johnson, William C.; Bond, Carl E. (1973) Records of the California tonguefish, threadfin shad and smooth alligator fish from Yaquina Bay, Oregon, California Fish and Game 59: 140-142

Lazzarro, Xavier (1987) A review of planktivorous species: Their evolution, feeding behaviours, selectivties and impacts., Hydrobiologia 146: 97-167

Lee, David S.; Gilbert, Carter R.; Hocutt, Charles H.; Jenkins, Robert E.; McAllister, Don E.; Stauffer, Jay R. (1980) Atlas of North American freshwater fishes, North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, Raleigh. Pp. <missing location>

Lee, David S.; Norden, Arnold; Gilbert, Carter, R.; Franz, Richard (1976) A list of the freshwater fishes of Maryland and Delaware, Chesapeake Science 17(3): 205-211

Lee, David S.; Platania, S. P.; Gilbert, Carter R.; Franz, Richard; Norden, Arnold (1981) A revised list of the freshwater fishes of Maryland and Delaware, Proceedings of the Southeastern Fishes Council 3(3): 1-9

Leidy, R. A. (2007) <missing title>, San Francisco Estuary Institute, Oakland. Pp. <missing location>

Lippson, Alice J.; Haire, Michael S.; Holland, A. Frederick; Jacobs, Fred; Jensen, Jorgen; Moran-Johnson, R. Lynn; Polgar, Tibor T.; Richkus, William (1979) Environmental atlas of the Potomac Estuary, Martin Marietta Corp., Baltimore, MD. Pp. <missing location>

Lippson, Alice J.; Moran, R. Lynn (1974) Manual for identification of early developmental stages of fishes of the Potomac River estuary., In: (Eds.) . , Baltimore MD. Pp. <missing location>

Matern, Scott A.; Moyle, Peter; Pierce, Leslie C. (2002) Native and alien fishes in a California estuarine marsh: twenty-one years of changing assemblages, Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 131: 797-816

Matern, Scott; Meng, Lesa; Pierce, Leslie C. (2001) Native and introduced larval fishes of Suisun Marsh, California: the effects of freshwater flow., Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 130: 750-765

Mejia, Francine; Saiki, Michael K.; Takekawa, John Y. (2008) Relation between species assemblages of fishes and water quality in salt ponds and sloughs in South San Francisco Bay, Southwestern Naturalist 53(3): 335-345

Meng, Lesa, Moyle, Peter B., Herbold, Bruce (1994) Changes in abundance and distribution of native and introduced fishes of Suisun Marsh, Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 123: 498-507

Menhinick, Edward F. (1991) The Freshwater Fishes of North Carolina, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, Raleigh. Pp. 45-203

Murdy, Edward O.; Birdsong, Ray S.; Musick, John A. (1997) Fishes of Chesapeake Bay, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.. Pp. 57-289

Nobriga, Matthew L.; Feyrer, Frederick (2008) Diet composition in San Francisco Estuary striped bass: does trophic adaptability have its limits?, Environmental Biology of Fishes 83(4): 495-503

Page, Lawrence M.; Burr, Brooks M. (1991) Freshwater Fishes: North America North of Mexico, Houghton-Mifflin, Boston. Pp. <missing location>

Parapar, Julio Martínez-Ansemil, Enrique Caramelo, Carlos Collado, Rut Schmelz, Rüdig (2009) Polychaetes and oligochaetes associated with intertidal rocky shores in a semi-enclosed industrial and urban embayment, with the description of two new species, Helgoland Marine Research 63: 293-308

DOI 10.1007/s10152-009-0158-7

Poole, Kathleen T. (1978) Subphylum Vertebrata. Fish, In: (Eds.) An Annotated Checklist of the Biota of the Coastal Zone of South Carolina. , Columbia. Pp. <missing location>

Randall, John E. (1987) Introductions of marine fishes to the Hawaiian Islands, Bulletin of Marine Science 41(2): 490-502

USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2003-2024 Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database. https://nas.er.usgs.gov/

Wang, Johnson C. S. (1986) Fishes of the Sacramento - San Joaquin Estuary and Adjacent Waters, California: A Guide to the Early Life Histories, IEP Technical Reports 9: 1-673

Yoklavich, Mary M.; Cailliet, Gregor M.; Barry, James P.; Ambrose, David A.; Antrim, Brooke S. (1991) Temporal and spatial patterns in abundance and diversity of fish assemblages in Elkhorn Slough, California., Estuaries 14(4): 465-480