Invasion History

First Non-native North American Tidal Record: 1952First Non-native West Coast Tidal Record: 1981

First Non-native East/Gulf Coast Tidal Record: 1952

General Invasion History:

Teredo bartschi is widespread in tropical and subtropical seas, and has been reported from Florida, Bermuda, throughout the Caribbean to Brazil, Hawaii, Australia, Iraq, Ghana, Kenya, and Fiji (Wallour 1960; Turner 1971; Barreto 2000; Borges et al. 2014a; Borges et al. 2014b). Although it was first described from the southeastern United States with type specimens from Tampa, Florida and occurrences reported from South Carolina to Texas (Clapp 1923), it is regarded as cryptogenic in Atlantic waters south of Cape Hatteras, and over most of its tropical-subtropical range (Carlton and Ruckelshaus 1997). Occurrences in the Pacific Coast of Mexico, California, the eastern Mediterranean, and Portugal are probable introductions (Abbott 1974; Hendrickx 1980; Borges et al. 2014a; Borges et al. 2014b).

North American Invasion History:

Invasion History on the West Coast:

Teredo bartschi was collected in Mexican Pacific waters in the Gulf of California in 1971 at La Paz, and in 1978 in Sinaloa, 30 km north of Mazatlan (Hendrickx 1980). It is known in California waters from specimens collected in San Diego in 1927, and in 2000 it was collected in Long Beach Harbor (Cohen et al. 2002). In the northern Pacific, shipworm specimens collected in 1981 in LadySmith Harbour (Vancouver Island, British Columbia) were identified originally as Lyrodus takanoshimensis but were re-examined and determined to be T. bartschi (Harbo et al. 2025). Populations of T. bartschi are established in Ladysmith Harbour and represent the northernmost Northeast Pacific record for this species (Harbo et al. 2025).

Invasion History on the East Coast:

Teredo bartschi is cryptogenic in the northwest Atlantic. Its northern breeding limit in the Western Atlantic was believed to be South Carolina (Clapp 1923; Turner 1971), but its range has been extended by transport via boats and by the heated effluents of power plants (Hoagland and Turner 1980; Hoagland 1986a). In 1944–52, it was found in test boards at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Portsmouth VA (Brown 1953). There are no further records from Chesapeake Bay. In 1973, breeding populations of T. bartschi were found in Barnegat Bay NJ, in Oyster Creek and Forked River, where they became very abundant, and damaging to wooden structures. These creeks were receiving heated effluent from the Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station (Hoagland and Turner 1980; Richards et al. 1984). The abundance of T. bartschi was reduced following a powerplant shutdown in the winter of 1979–1980 (Richards et al. 1984). This shipworm has not been collected to our knowledge since 1982 (Hoagland 1986a; Hillman et al. 1990; Carlton 1992). In 1979, it was found in thermal effluents of the Millstone Nuclear Power Plant Waterford, Connecticut (Hoagland 1986a; Hoagland 1986b). The populations here remained small (Hoagland 1986b) and were no longer present by 2000 (James T. Carlton, personal communication 2000). These isolated populations of subtropical shipworms are very vulnerable to winter shutdowns of powerplants and are likely to be sporadic.

Invasion History in Hawaii:

Teredo bartschi was found in Hilo Harbor, Hawaii and at Pearl Harbor, Oahu both in 1935 (Edmondson 1942 cited by Turner 1966, Coles et al. 1999b; Carlton and Eldredge 2009). It has also been collected at Midway Island (Wallour 1960).

Invasion History Elsewhere in the World:

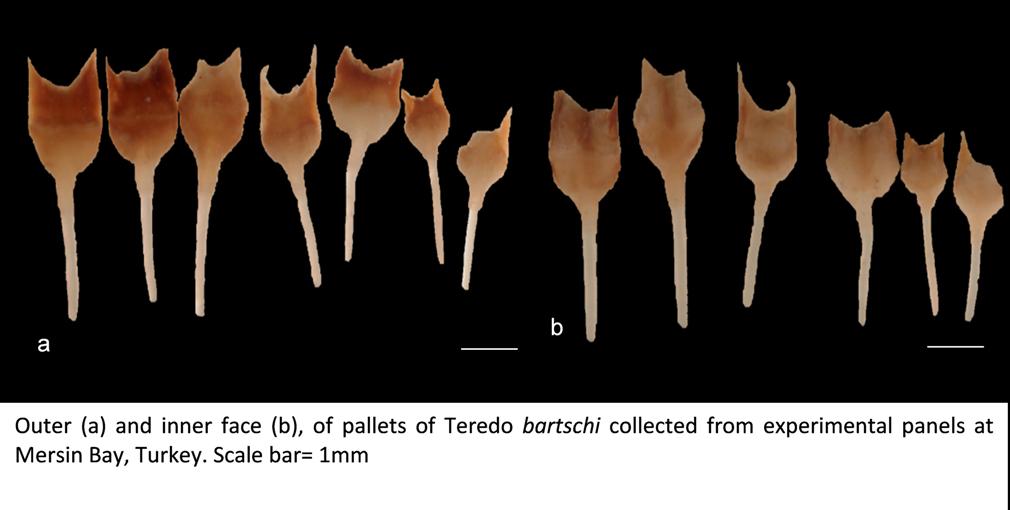

On the Atlantic coast of Europe, T. bartschi was found to be established in the Ria Formosa, Olhao, Portugal, in the Gulf of Cadiz, in 2002 (Borges et al. 2014a). It was first found in the Mediterranean in Port Said, Egypt, at the mouth of the Suez Canal in 1935 (Roch 1935, cited by Turner 1966); and has been found in Mersin Turkey, on the Levantine Coast 2002–2003 (Borges et al. 2014a). In 2002, T. bartschi was collected in the Lagoon of Venice and has survived at least through to 2017 despite temperatures near 0°C (Tagliapetra et al. 2021). The range of this shipworm can be expected to expand with rising sea temperatures.

Description

Teredo bartschi belongs to the family Teredinidae (shipworms), which are highly modified mollusks, hardly recognizable as bivalves, and adapted for boring into wood. The shell is reduced to two small, ridged valves covering the head, and used for grinding and tearing wood fibers. The body is naked and elongated and ends with two siphons protected by elaborate calcareous structures called pallets (Turner 1966). In T. bartschi, the shell resembles that of the Naval Shipworm (T. navalis), but is smaller, with the auricle of the shell semicircular rather than subtriangular. The pallets have a long stalk, with a short blade deeply excavated at the tip, forming a U-shape. The distal third of the cap is made of periostracum, which is light golden to dark brown and semitransparent, extending at the corners to form small horns. The calcareous base can be seen through the periostracum and resembles an hourglass. Description from: Turner 1966; Turner 1971; Abbott 1974.

The type specimen ofT. bartschi had a shell 4.2 mm long and 4 mm high, while the pallets were 5 mm long with a stalk 3 mm long (Clapp 1923). Teredo bartschi can reach maturity at a length of 4mm and reach a maximum size of 132mm in Barnegat Bay, New Jersey (Hoagland 1983).

Potentially misidentified species—The diversity of shipworms in tropical waters is very great. Many are now widely distributed in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, largely because of shipping. The species listed below have been reported from Florida, the Caribbean, the West Coast of North America, or Hawaiian waters.

Taxonomy

Taxonomic Tree

| Kingdom: | Animalia | |

| Phylum: | Mollusca | |

| Class: | Bivalvia | |

| Subclass: | Heterodonta | |

| Order: | Myoida | |

| Superfamily: | Pholadoidea | |

| Family: | Teredinidae | |

| Genus: | Teredo | |

| Species: | bartschi |

Synonyms

Teredo balatro (Iredale, 1932)

Teredo batilliformis (Clapp, 1924)

Teredo fragilis (Tate, 1888)

Teredo grobba (Moll, 1937)

Teredo hiloensis (Edmondson, 1942)

Teredo shawi (Iredale, 1932)

Potentially Misidentified Species

Cosmopolitan, tropical, subtropical

Lyrodus floridanus

W Atlantic, subtropical

Lyrodus pedicellatus

Cosmopolitan, tropical-warm temperate, a species complex

Teredo clappi

Cosmopolitan, tropical, subtropical

Teredo fulleri

Cosmopolitan, tropical

Teredo furcifera

Cosmopolitan, tropical, subtropical

Teredo johneoni

Cosmopolitan, tropical, subtropical

Teredo navalis

Cosmopolitan, tropical-cold temperate

Ecology

General:

Shipworms dig long burrows in submerged wood in marine environments. They burrow by rocking and abrading the wood fibers. The mantle covers most of the length of their body and secretes a calcareous lining along the interior of the burrow. They normally have their anterior end with head and shells inside the burrow, and their siphons protruding. The pallets plug the burrow when the siphons are retracted (Barnes 1983).

Shipworms are protandrous hermaphrodites, beginning life as male and transforming to female, but they have no capacity for self-fertilization. Males release sperm into the water column which fertilizes eggs for the female. The fertilized eggs are then brooded in the gills. Larvae are retained in the gills to the veliger stage (Hoagland 1986a; Richards et al. 1984). The larvae of Teredo bartschi are planktonic for about 3 days. They settle in the pediveliger stage, and then rapidly metamorphose and begin boring into wood within 2-3 days. They quickly develop a calcified shell, pallets, and burrow lining (Turner and Johnson 1971). Shipworms may obtain some (or most, Paalvast and van der Velde 2013) of their nutrition from plankton, but some comes from wood, which consists of cellulose. Symbiotic bacteria fix nitrogen, essential for protein synthesis (Turner and Johnson 1971; Barnes 1983).

Teredo bartschi is known from fixed wood structures, panels, driftwood, and mangroves in tropical and subtropical climates, and in heated power plant effluents in temperate estuaries (Wallour 1960; Hoagland and Turner 1980; Ibrahim 1981; Hoagland 1983; Singh and Sasekumar 1994). Teredo bartschi is sensitive to low temperatures. There was only 18–20% survival of newly settled juveniles at 10°C and adults became inactive at 13–17°C and died at 3°C (Hoagland 1986a). In temperate regions, its survival is dependent on warm effluent waters. Adult shipworms can tolerate salinities as low as 7 PSU (Hoagland 1986a) and as high as 45 PSU (Cragg et al. 2009). Larvae, reared at 22 PSU and 24°C, survived transfer to 12 and 35 PSU, and to 20 and 3°C (Hoagland 1986a).

Food:

Phytoplankton, Wood

Trophic Status:

Suspension Feeder

SusFedHabitats

| General Habitat | Coarse Woody Debris | None |

| General Habitat | Marinas & Docks | None |

| General Habitat | Vessel Hull | None |

| General Habitat | Mangroves | None |

| Salinity Range | Mesohaline | 5-18 PSU |

| Salinity Range | Polyhaline | 18-30 PSU |

| Salinity Range | Euhaline | 30-40 PSU |

| Tidal Range | Subtidal | None |

| Tidal Range | Low Intertidal | None |

Life History

Tolerances and Life History Parameters

| Minimum Temperature (ºC) | 5 | Field: Italy, Lagoon of Venice (Tagliapietra et al. 2021)Experimental- There was only 18-20% survival of newly settled juveniles at 10 C and adults became inactive at 13-17 C and died at 3 C (Hoagland 1986a). |

| Maximum Temperature (ºC) | 35 | Experimental (Hoagland 1986a). |

| Minimum Salinity (‰) | 7 | Experimental (Hoagland 1986a). |

| Maximum Salinity (‰) | 45 | Experimental (Hoagland 1986a). |

| Minimum Dissolved Oxygen (mg/l) | 0 | Teredo bartschi is presumed, like T. navalis, to survive anoxic conditions for extended periods by using stored glycogen. Teredo navalis can survive 6 weeks sealed in burrows, but prolonged low O2 can interfere with feeding and reduce infestations (Richards et al. 1984). |

| Minimum Reproductive Temperature | 20 | Experimental (Hoagland 1986a). |

| Maximum Reproductive Temperature | 35 | Experimental (Hoagland 1986a). |

| Minimum Reproductive Salinity | 12 | Experimental (Hoagland 1986a). |

| Maximum Reproductive Salinity | 35 | Experimental (Hoagland 1986a). |

| Minimum Duration | 3 | Larvae |

| Minimum Length (mm) | 4 | Minimum mature size, Barnegat Bay NJ (Hoagland 1983). |

| Maximum Length (mm) | 132 | Barnegat Bay NJ (Hoagland 1983). |

| Broad Temperature Range | None | Warm temperate-Tropical |

| Broad Salinity Range | None | Mesohaline-Euhaline |

General Impacts

Teredo bartschi is one of many shipworms contributing to the rapid riddling of wood in tropical and subtropical waters. Its impacts in these warm waters are difficult to assess, because of the diversity of the shipworm community. However, in the temperate waters of New Jersey where it was restricted to areas warmed by thermal effluents, it reached high abundance and caused extensive damage to marinas near the Oyster Creek Nuclear Power Plant in Barnegat Bay (Turner 1973; Hoagland and Turner 1980).

Regional Impacts

| NA-ET3 | Cape Cod to Cape Hatteras | Economic Impact | Shipping/Boating | ||

| The warm effluents of Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station (NJ) dramatically raised temperatures and salinities in parts of Barnegat Bay, resulting in the invasion of shipworms including Teredo bartschi into previously unaffected areas, causing severe damage to docks and pilings in marinas (Turner 1973; Hoagland and Turner 1980; Hoagland 1983; Richards et al. 1984). | |||||

| M070 | Barnegat Bay | Economic Impact | Shipping/Boating | ||

| The warm effluents of Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station (NJ) dramatically raised temperatures and salinities in parts of Barnegat Bay, resulting in the invasion of shipworms including Teredo bartschi into previously unaffected areas, causing severe damage to docks and pilings in marinas (Turner 1973; Hoagland and Turner 1980; Hoagland 1983; Richards et al. 1984). | |||||

| NJ | New Jersey | Economic Impact | Shipping/Boating | ||

| The warm effluents of Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station (NJ) dramatically raised temperatures and salinities in parts of Barnegat Bay, resulting in the invasion of shipworms including Teredo bartschi into previously unaffected areas, causing severe damage to docks and pilings in marinas (Turner 1973; Hoagland and Turner 1980; Hoagland 1983; Richards et al. 1984). | |||||

Regional Distribution Map

Non-native

Native

Cryptogenic

Failed

Occurrence Map

References

Abbott, R. Tucker (1974) American Seashells, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York. Pp. <missing location>Barnes, Robert D. (1983) Invertebrate Zoology, Saunders, Philadelphia. Pp. 883

Barreto, Cristine C.; Junqueira, Andrea O. R.; da Silva, Sérgio Henrique G. (2000) The effect of low salinity on teredinids, Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology 43(4): published online

Borges, L. M. S. (2013) Biodegradation of wood exposed in the marine environment: Evaluation of the hazard posed by marine wood-borers in fifteen European sites, International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 96: 97-104

Borges, Luísa M. S.; Merckelbach, Lucas M.; Sampaio, Íris; Cragg, Simon M. (2014b) Diversity, environmental requirements, and biogeography of bivalve wood borers (Teredinidae) in European coastal waters, Frontiers in Zoology 11(13): Published online

Borges. Luísa M. S.; Sivrikaya, Huseyin; Cragg, Simon M. (2014a) First records of the warm water shipworm Teredo bartschi Clapp, 1923 (Bivalvia, Teredinidae) in Mersin, southern Turkey and in Olhão, Portugal, Bioinvasions Records 3(1): 25-28

Brown, Dorothy J. (1953) <missing title>, Report No. 8511 William F. Clapp Laboratories, Inc., Duxbury, Massachusetts. Pp. <missing location>

Calder, Dale R. (2019) On a collection of hydroids (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) from the southwest coast of Florida, USA, Zootaxa 4689(1): 1-141

Carlton, James T. (1979) History, biogeography, and ecology of the introduced marine and estuarine invertebrates of the Pacific Coast of North America., Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Davis. Pp. 1-904

Carlton, James T. (1992) Introduced marine and estuarine mollusks of North America: An end-of-the-20th-century perspective., Journal of Shellfish Research 11(2): 489-505

Carlton, James T.; Eldredge, Lucius (2009) Marine bioinvasions of Hawaii: The introduced and cryptogenic marine and estuarine animals and plants of the Hawaiian archipelago., Bishop Museum Bulletin in Cultural and Environmental Studies 4: 1-202

Carlton, James T.; Ruckelshaus, Mary H. (1997) Nonindigenous marine invertebrates and algae of Florida, In: Simberloff, Daniel, Schmitz, Don C., Brown, Tom C.(Eds.) Strangers in Paradise: Impact and Management of Nonindigenous Species in Florida. , Washington, D.C.. Pp. 187-201

Çinar, Melih Ertan and 7 authors (2021) Current status (as of end of 2020) of marine alien species in Turkey, None 16: Published online

Clapp, William F. (1923) New species of Teredo from Florida, Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History 37: 31-38

Cohen, Andrew N. and 12 authors (2002) Project report for the Southern California exotics expedition 2000: a rapid assessment survey of exotic species in sheltered coastal waters., In: (Eds.) . , Sacramento CA. Pp. 1-23

Coles, S. L.; DeFelice, R. C.; Eldredge, L. G.; Carlton, J. T. (1999b) Historical and recent introductions of non-indigenous marine species into Pearl Harbor, Oahu, Hawaiian Islands., Marine Biology 135(1): 147-158

Cragg, S.M.; Jumel, M.-C.; Al-Horani, F.A.; Hendy, I.W. (2009) The life history characteristics of the wood-boring bivalve Teredo bartschi are suited to the elevated salinity, oligotrophic circulation in the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea, Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 375: 99-105

Cruz, Manuel; Torres, Glasys; Villamar, Felicia (1989) Comparative study of the woodboring bivalves of the more resistant woods (Laurel, 'Moral', Cow Tree) and the more vulnerable (Mangrove) on the coast of Ecuador], Acta Oceanografica del Pacifico 5(1): 49-55

Harbo RM, MacIntosh H, Treneman NC (2025) A report of two non-native shipworms (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Teredinidae) in the warm waters of Ladysmith Harbour, British Columbia, Canada, Canadian Journal of Zoology 103: 1-8

https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/cjz-2024-0127.

Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology 2008-2021 Museum of Comparative Zoology Collections database- Malacology Collection. <missing URL>

Hendrickx, Michel E. (1980) Range extensions of three species of Teredinidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia) along the Pacific coast of America, The Veliger 23(1): 93-94

Hillman, Robert E. (1979) Occurrence of Minchinia sp. in species of the molluscan borer, Teredo, Marine Fisheries Review 41(1): 21-24

Hillman, Robert E.; Ford Susan E.; Haskin, Harold H. (1990) Minchinia teredinis n. sp. (Balanosporida, Haplosporidiidae), a parasite of teredinid shipworms, Journal of Protozoology 37(5): 364-368

Hillman, Robert E.; Maciolek, Nancy J.; Lahey, Joanne I.; Melmore, C. Irene (1982) Effects of a haplosporidian parasite, Haplosporidium sp., on species of the molluscan woodborer Teredo in Barnegat Bay, New Jersey., Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 40: 307-319

Hoagland, K, Elaine (1986b) Genetic variation in seven wood-boring teredinid and pholadid bivalves with different patterns of life history and dispersal, Malacologia 27(2): 323-339

Hoagland, K. E.; Turner, R. D. (1980) Range extensions of teredinids (shipworms) and polychaetes in the vicinity of a temperate-zone nuclear generating station., Marine Biology 58(1): 55-64

Hoagland, K. Elaine (1983) Life history characteristics and physiological tolerances of Teredo bartschi, a shipworm introduced into two temperate zone nuclear power plant effluents., In: Sengupta, N. S., and Lee S. S.(Eds.) Third International Waste Heat Conference.. , Miami Beach, FL. Pp. 609-622

Hoagland, K. Elaine (1986a) Effects of temperature, salinity, and substratum on larvae of the shipworms Teredo bartschi Clapp and T. navalis Linnaeus (Bivalvia: Teredinidae), American Malacological Bulletin 4(1): 89-99

Ibrahim, J. V. (1981) Season of settlement of a number of shipworms (Mollusca: Bivalvia) in six Australian harbors., Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 32: 591-604

Joseph, Edwin B.; Nichy, Fred E (1955) Literature survey of the Jacksonville Harbor area. Part III. Algae, marine fouling and boring organisms., Florida State University Oceanographic Institute Contribution 36: 1-20. Florida State University Oceanographic Institute Contribution 36: 1-20. Florida State University Oceanographic Institute Contribution 36: 1-20

Junqueira, Andrea D. O. R.; da Silva, Sergio Henrique G; Silva, Marian Julia M. (1989) [Evaluation of the intensity and diversity of Teredinae (Mollusca - Bivalvia) along the coast of Rio de Janeiro, State Brazil), Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz Rio de Janeiro 84(Suppl. 4): 275-280

Karatayev A, Claudi R, Lucy F (2012) History of Dreissena research and the ICAIS gateway to aquatic invasions research, Aquatic Invasions 7(1): 1–5

https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2012.7.1.001

Leonel, Rosa Maria Veiga; Godoy, Lopes, B.C.; Aversari, Marcos (2002) Distribution of wood-boring bivalves in the Mamanguape River estuary, Paraiba, Brazil, Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 82: 1039-1040

Lomonaco, Cecilia; Santos, Andre S.; Christoffersen, Martin l. (2011) Effects of local hydrodynamic regime on the individual’s size in intertidal Sabellaria (Annelida: Polychaeta: Sabellariidae) and associated fauna at Cabo Branco beach, north-east Brazil, Marine Biodiversity Records 4(e76): Published online

doi:10.1017/S1755267211000807;

Low-Pfeng, Antonio; Recagno, Edward M. Peters (2012) <missing title>, Geomare, A. C., INESEMARNAT, Mexico. Pp. 236

Maldonado, Gustavo Carvalho; Skinner, Luis Felipe (2016) Differences in the distribution and abundance of Teredinidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia) along the coast of Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil, Brazilian Journal of Oceanography 64(4): Published online

Nair, N. Balakrishnan (1984) The problem of marine timber destroying organisms along the Indian coast, Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences 93(3): 203-223

Nepal, Vaskar; Fabrizio, Mary C. (2020) Sublethal effects of salinity and temperature on non-native blue catfish: Implications for establishment in Atlantic slope drainages, None 15(12): e0244392

Paalvast, Peter; van der Velde, Gerard (2013) What is the main food source of the shipworm Teredo navalis? A stable isotope approach, Journal of Sea Research 80: 58-60

Pati, M. V.; Rao, M. V.; Balaji, M.; Swain, D. (2012) Growth of wood borers in a polluted Indian harbour, World Journal of Zoology 7: 210-215

Quintanilla, Elena; Thomas Wilke; Ramırez-Portilla, Catalina; Sarmiento, Adriana; Sanchez, Juan A. () , None <missing volume>: <missing location>

Quintanilla, Elena; Thomas Wilke; Ramırez-Portilla, Catalina; Sarmiento, Adriana; Sanchez, Juan A.2017 (2017) Taking a detour: invasion of an octocoral into the Tropical Eastern Pacific, Biological Invasions <missing volume>(17): 2583–2597

DOI 10.1007/s10530-017-1469-2

Rai Singh, Harinder Sasekumar, A. (1994) Distribution and abundance of marine wood borers on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia., Hydrobiologia 285: 111-121

Rai Singh, Harinder; Sasekumar, A. (1996) Wooden panel deterioration by tropical marine wood borers, Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 42: 755-769

Richards, Beatrice R.; Hillman, Robert E.; Maciolek, Nancy J. (1984) Shipworms, In: Kennish, Michael J.; Lutz, Richard A.(Eds.) Lecture Notes on Coastal and Estuarine Studies - Ecology of Barnegat Bay, New Jersey. , New York. Pp. 201-225

Ruiz, Gregory M.; Geller, Jonathan (2018) Spatial and temporal analysis of marine invasions in California, Part II: Humboldt Bay, Marina del Re, Port Hueneme, and San Francisco Bay, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center & Moss Landing Laboratories, Edgewater MD, Moss Landing CA. Pp. <missing location>

Savva, Ioannis; Bennett, Scott; Roca, Guillem; Jordà, Gabriel; Marbà, Nuria (2018) Thermal tolerance of Mediterranean marine macrophytes; Vulnerability to global warming, Ecology and Evolution 8: 12032-12043.

Srinivasan, V. V. (1968) Notes on the distribution of wood-boring teredines in the tropical Indo-Pacific, Pacific Science 12: 277-280

Tagliapietra, Davide; Guarneri , Irene; Keppel, Erica; Sigovini, Marco (2021) After a century in the Mediterranean, the warm-water shipworm Teredo bartschi invades the Lagoon of Venice Italy), overwintering a few degrees above zero, Biological Invasions 23: 1595-1618

Tagliapietra, Davide; Keppel, Erica; Sigovini, Marco; Lambert, Gretchen (2012) First record of the colonial ascidian Didemnum vexillum Kott, 2002 in the Mediterranean: Lagoon of Venice (Italy), Bioinvasions Records 1: in press

Turner, R. D. (1973) In the path of a warm, saline effluent, American Malacological Union Bulletin 39: 36-39

Turner, R. D.; Johnson, A. C. (1971) Marine Borers, Fungi, and Fouling Organisms of Wood, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris. Pp. 259-301

Turner, Ruth D. (1966) A survey and illustrated catalogue of the Teredinidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia), The Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge. Pp. <missing location>

U.S. National Museum of Natural History 2002-2021 Invertebrate Zoology Collections Database. http://collections.nmnh.si.edu/search/iz/

Wallour, Dorothy Brown (1960) Thirteenth progress report on marine borer activity in test boards operated during 1959, William F. Clapp Laboratories, Duxbury, Massachusetts. Pp. 1-41