Invasion History

First Non-native North American Tidal Record: 1927First Non-native West Coast Tidal Record:

First Non-native East/Gulf Coast Tidal Record: 1927

General Invasion History:

Paracerceis sculpta was described from San Diego and San Clemente Island, California, and later found from Southern California and the Pacific Coast of Mexico, including the Gulf of California (Richardson 1905; Menzies 1962; Schultz 1969; Espinosa and Hendrickx 2001). It has also been collected in Ecuador (US National Museum of Natural History 2016). It has been widely introduced around the world, in warm-temperate-to-tropical harbors, on every continent, except Antarctica. Although this isopod has probably been overlooked in some locations, the many recent discoveries of P. sculpta suggest that it has been transported to many places since the mid-20th century (Rodriguez et al. 1992; Hewitt and Campbell 2001).

North American Invasion History:

Invasion History on the East Coast:

In 1996, 29 specimens of Paracerceis sculpta were collected at two locations, Fort Pierce and Sebastian Inlet, on the Indian River Lagoon, Florida (USNM 285258, USNM 285259, US National Museum of Natural History 2016). The animals were found on floating docks and ropes, in fouling communities (‘Caulerpa, sponges, hydroids, Porites, coralline algae, and tunicates'). Marilyn Schotte, of the Museum, confirmed the identification (personal communication, 2009). We consider P. sculpta to be established in the Indian River Lagoon.

Invasion History on the Gulf Coast:

In 2009, a population of P. sculpta was found in Port Aransas, Texas, in crevices in oyster reefs (Munguia and Shuster 2013). It is likely that this isopod is more widespread along the Atlantic Coast of Florida and the Gulf of Mexico, but is overlooked due to confusion with the similar, native, P. caudata.

Invasion History in Hawaii:

Paracerceis sculpta was found in a survey of isopods and tanaiids on buoys in Pearl Harbor, Oahu, and Hilo Harbor, Hawaii, in 1943. It was considered likely to have been transported on naval ships from San Diego (Miller 1968). It was also found in Kaneohe Bay, Oahu in 1962 (USNM 107929, US National Museum of Natural History 2016), and in Port Allen Harbor, Kauai in 2002 (Coles 2004).

Invasion History Elsewhere in the World:

Paracerceis sculpta was first found in São Sebastião, São Paulo state, Brazil, in 1978 (Pires 1981). It has been found from Santa Catarina state north to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Pires et al. 1981; de Loyola e Silva 2005). Elsewhere in the Western Atlantic, one specimen of P. sculpta was found in a yacht club in Bermuda in 2013 (Ruiz et al., unpublished data, Kim Holzer, personal communication).

In the Mediterranean, P. sculpta was first reported from the Lake of Tunis, Tunisia (Rezig et al. 1978, cited by Tlig-Zuoari et al. 2009 and Amor et al. 2016). Records from the Mediterranean are spotty. In 1983-1985, it was reported from several locations in Italy, the Venice Lagoon in the Adriatic, the Lake of Caprolace (Tyrhennian Sea), the Mar Piccolo, Gulf of Taranto and the Harbor of Augusta, Sicily (Ionian Sea). These records were mostly from confined lagoon or harbor habitats (Forniz and Maggiore 1985). In 1995, it was collected on sandy beaches off Catalonia, Spain (Munilla and San Vicente 2004). On the open Atlantic coast, it was found in the Gulf of Cadiz, Spain in 1988 (Rodriguez et al. 1992, Castello and Carballo 2002).

Paracerceis sculpta has several widely separated invasions in the Indian Ocean and western Pacific. It was found to be established in Pakistan (Javed 2001), South Africa (Port Elizabeth, Griffiths et al. 2005), and the Seto Inland Sea, Japan (in 1986, Ariyama and Otani 2004, cited by Lutaenko et al. 2014). One male specimen was collected from Hong Kong in 1986 (Li and Li 2003). Paracerceis sculpta was first found in Australian waters in Townsville, Queensland, in 1975; and later in Sydney Harbour, New South Wales, in 1984; Port Philip Bay, Adelaide, South Australia, in 2000, and Bunbury, Western Australia, in 1999 (Hewitt and Campbell 2001). This isopod was found on wharf pilings, among algae, fan worms, and sponges (Hewitt and Campbell 2001).

Description

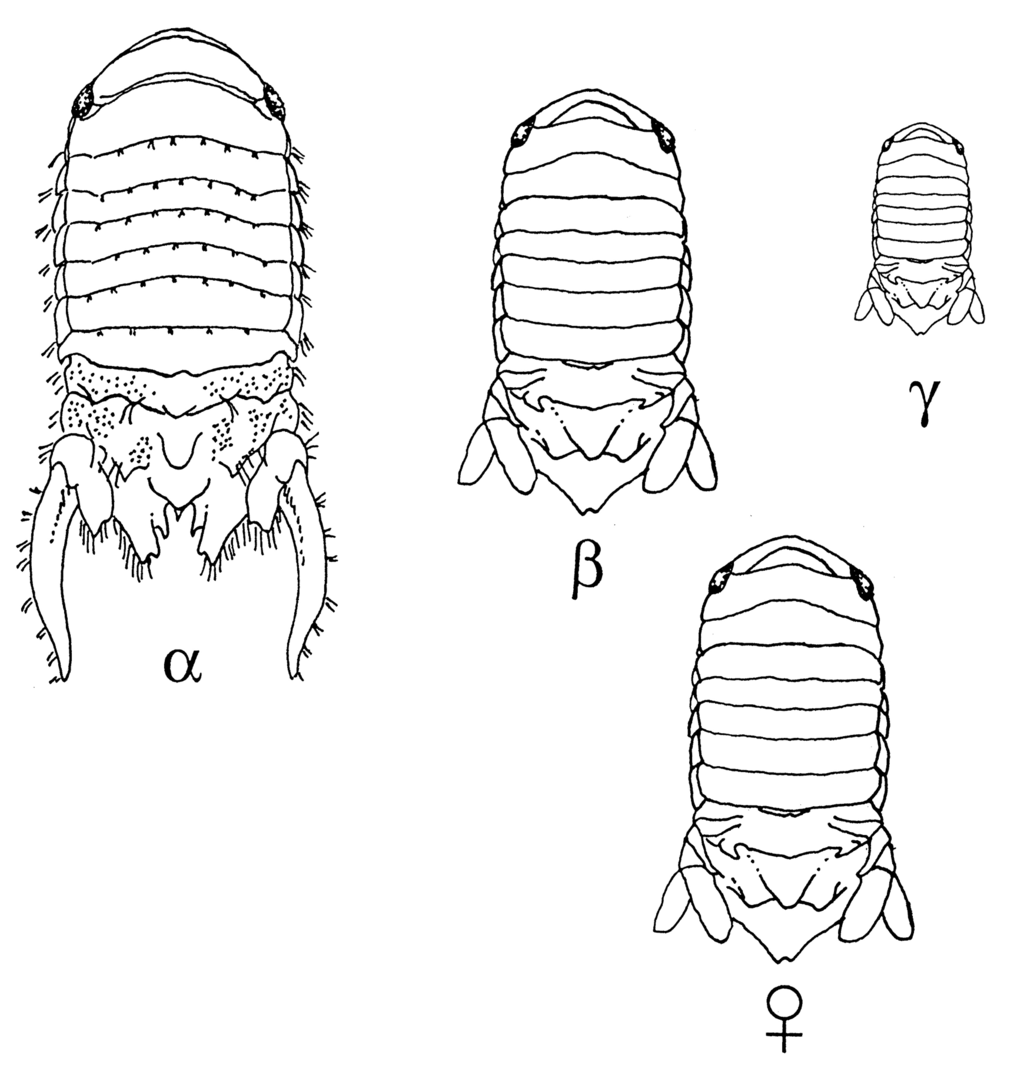

The Paracerceis genus shows strong sexual dimorphism, with uropods developed into long caudal processes, and a deep indentation in the apex of the pleotelson, in males. In females, the telson is simple and the isopods are less ornamented. They have a crescent-shaped head, which is wider than it is long, with prominent eyes, an oval-rectangular body, and a broad, roughly triangular pleotelson (female) or a deep slit with an elaborately curved outline (male). The anterior end of the slit has a short median tooth in P. sculpta. In large (alpha) males, the exopod of the uropod is greatly extended (~1/3 of body length), and more than twice as long as the endopod. The exopods and endopods have clusters of bristles, but do not bear spines. The endopod does not reach the apex of the pleotelson (Menzies 1962; Schultz 1969; Shuster 1987; Harrison and Ellis 1991; Brusca 2007). In females, the telson is roughly triangular and usually has an apical notch (Schultz 1969; Pires 1980; Rodriguez et al. 1992). [However, Brusca et al.'s (2007) illustration shows the female telson ending in a rounded tip, so this feature may be variable.] In females, the uropods are not modified, with the exopods and endopods nearly equal in length. Males, in species descriptions, range from 4.4 to 9.0 mm, and females from 3.0 to 8.5 mm (Pires 1989; Rodriguez et al. 1992; Espinosa and Hendrickx 2002).

Males of Paracerceis sculpta, in the Gulf of California, guard harems of females and compete intensely for mates in the cavities of sponges. They can develop into one of three morphotypes associated with different mating strategies. Alpha males are the largest, ~5-8 mm, and have the elaborate elongated uropods described above. Beta males resemble females in shape, and are 3-5 mm long, and lack elongated uropods. Gamma males are 2-3 mm long. These morphologies are associated with aggressive guarding, female mimicry, and 'sneaking', respectively (Shuster 1987). The alpha males are normally the ones included and illustrated in species descriptions (Schultz 1969; Pires 1989; Rodriguez et al. 1992; Espinosa and Hendrickx 2002).

Taxonomy

Taxonomic Tree

| Kingdom: | Animalia | |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda | |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea | |

| Class: | Malacostraca | |

| Subclass: | Eumalacostraca | |

| Superorder: | Peracarida | |

| Order: | Isopoda | |

| Suborder: | Flabellifera | |

| Family: | Sphaeromatidae | |

| Genus: | Paracerceis | |

| Species: | sculpta |

Synonyms

Cilicaea sculpta (Richardson, 1904)

Paracerceis sculpta (Menzies, 1962)

Sergiella angra (Pires, 1980)

Potentially Misidentified Species

Paracerceis caudata ranges from New Jersey to Brazil in seagrasses and corals. The male of this isopod has two median teeth in the anterior end of the slit in the pleotelson (Schultz 1969).

Paracerceis cordata

Paracerceis cordata ranges from Alaska to southern California, found from the intertidal to 55 m (Schultz 1969; Brusca et al. 2007).

Ecology

General:

As with most isopods, Paracerceis sculpta has separate sexes and fertilization is internal. The young are brooded by the female and development is direct. It commonly lives in dense colonies, where one or few males occur with a harem of females. In Gulf of California populations, males occur in three morphotypes, associated with different mating strategies. Alpha males are the largest, ~5-8 mm, and have elaborate elongated uropods. Beta males resemble females in shape, and are 3-5 mm long, and lack the elongated uropods. Gamma males are 2-3 mm long. These morphologies are associated with aggressive guarding, female mimicry, and 'sneaking', respectively (Shuster 1987). Competition for females appears to be strong among alpha males, with most guarding 0-1 females, but a few up to 12 females. The polymorphism appears to be controlled by the interaction of three genes which interact to affect sex and morphology (Shuster and Sassaman 1997). In introduced populations, only alpha-males and females have been reported, to our knowledge (Forniz and Maggiore 1985; Hewitt and Campbell 2001; Pires 1980; Munguia and Shuster 2013). Females maintained with a single alpha male produced 40 to 120 live juveniles each. When a male was maintained with four females, in an artificial sponge, females produced 30-90 juveniles (Shuster 1995).

Paracerceis sculpta is widespread in warm-temperate to tropical climates (13-30°C), and polyhaline to hyperhaline salinities (28-46 PSU, Rodriguez et al. 1992; Espinosa and Henidrickx 2002). It is known from a wide range of habitats, including the interiors of invertebrates, seaweeds, wharf pilings, rock crevices, but also from soft sediments. In its native and invaded regions, its colonized calcareous sponges (Espinosa-Pérez and Hendrickx 2001). In Brazil, it has been found in seaweed communities (Sargassum and Galaxaura spp.) (Pires 1980; Loyola e Silva et al. 1999). In Australia, it was found in wharf pilings and pontoons, often associated with sponges and fan worms (Hewitt and Campbell 2001), and also on hulls of naval ships (Montelli and Lewis 2008). In Pacific Mexico, it was found on mangrove roots (Espinosa-Pérez and Hendrickx 2001). In Texas, P. sculpta occurs in the crevices of oyster reefs (Munguia and Shuster 2013). This isopod has also been collected from mud bottoms (Rodriguez et al. 1992). Juvenile isopods probably feed by scraping algae off surfaces (Brusca et al. 2007). Shuster (1987) cultured P. sculpta using a benthic diatom, Amphiprora sp., as food.

Food:

Diatoms, detritus, algae

Trophic Status:

Herbivore

HerbHabitats

| General Habitat | Marinas & Docks | None |

| General Habitat | Rocky | None |

| General Habitat | Mangroves | None |

| General Habitat | Grass Bed | None |

| General Habitat | Unstructured Bottom | None |

| General Habitat | Vessel Hull | None |

| General Habitat | Oyster Reef | None |

| Salinity Range | Polyhaline | 18-30 PSU |

| Salinity Range | Euhaline | 30-40 PSU |

| Tidal Range | Subtidal | None |

| Tidal Range | Low Intertidal | None |

| Vertical Habitat | Epibenthic | None |

Tolerances and Life History Parameters

| Minimum Temperature (ºC) | 13 | Field, Spain (Rodriguez et al, 1992) |

| Maximum Temperature (ºC) | 29.8 | Field, Mexico, Pacific (Espinosa and Henidrickx 2002) |

| Minimum Salinity (‰) | 28 | Field, Venice, Italy, Pacific (Espinosa and Henidricks 2002) |

| Maximum Salinity (‰) | 46 | Field, Mexico, Pacific (Espinosa and Henidrickx 2002) |

| Maximum Length (mm) | 9 | Male, Pacific Mexico Espinosa and Hendrickx 2002 |

| Broad Temperature Range | None | Warm temperate-Tropical |

| Broad Salinity Range | None | Polyhaline-Hyperhaline |

General Impacts

Although Paracerceis sculpta is a widely distributed marine invader, no ecological or economic impacts have been reported.Regional Distribution Map

Non-native

Native

Cryptogenic

Failed

Occurrence Map

References

Amor, Kounofi-Ben; Rifi, M.; Ghanem, R.; Draief, I.; Zouali, J.; Souissi, J. Ben (2016) Update of alien fauna and new records of Tunisian marine fauna, Mediterranean Marine Science 17(1): 124-143Associated Press (12/2021) Lummi Nation declares disaster after invasive crab arrives, Seattle Times <missing volume>: <missing location>

Bleile, Nadine; Thieltges, David W. 2021 Prey preferences of invasive (Hemigrapsus sanguineus, H. takanoi) and native (Carcinus maenas) intertidal crabs in the European Wadden Sea. <missing URL>

Boltovskoy D, Paolucci E, MacIsaac HJ, Zhan A, Xia Z, Correa N (2022) What we know and don’t know about the invasive golden mussel Limnoperna fortunei, Hydrobiologia 852: 1275–1322

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-022-04988-5

Brusca, Richard C.; Coeljo, Vania R. Taiti, Stefano (2007) The Light and Smith Manual: Intertidal invertebrates from Central California to Oregon (4th edition), University of Calfiornia Press, Berkeley CA. Pp. 503-542

Carlton, James T.; Eldredge, Lucius (2009) Marine bioinvasions of Hawaii: The introduced and cryptogenic marine and estuarine animals and plants of the Hawaiian archipelago., Bishop Museum Bulletin in Cultural and Environmental Studies 4: 1-202

Castelló, José; Carballo, José Luis (2001) Isopod fauna, excluding Epicaridea, from the Strait of Gibraltar and nearby areas (Southern Iberian Peninsula)*, Scientia Marina 65(3): 221-241

Çinar, Melih Ertan and 7 authors (2021) Current status (as of end of 2020) of marine alien species in Turkey, None 16: Published online

Coles, S. L.; DeFelice, R. C.; Eldredge, L. G.; Carlton, J. T. (1999b) Historical and recent introductions of non-indigenous marine species into Pearl Harbor, Oahu, Hawaiian Islands., Marine Biology 135(1): 147-158

Coles, S. L.; Reath, P. R.; Longenecker, K.; Bolick, Holly; Eldredge, L. G. (2004) <missing title>, Hawai‘i Community Foundation and the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Honolulu. Pp. 1-187

de Loyola e Silva, Jayme; Masunari, Setuko; Dubiaski-Silva, Janete; (1999) [Redescription of Paracerceis sculpta (Holmes 1994) (Crustacea, Isopoda, Sphaeromatidae) and new occurrence at Bombinhas, Santa Catarina, Brazil.], Acta Biologia Paranense 28: 109-124

Farrapeira, Cristiane Maria Rocha; Tenório, Deusinete de Oliveira ; do Amaral, Fernanda Duar (2011) Vessel biofouling as an inadvertent vector of benthic invertebrates occurring in Brazil, Marine Pollution Bulletin 62: 832-839

Forniz, C.; Maggiore, F. (1985) New records of Sphaeromatidae from the Mediterranean Sea (Crustacea, Isopoda )., Oebalia 11(3): 779-783

Griffiths, Charles L.; Robinson, Tamara B.; Mead, Angela (2009) Biological Invasions in Marine Ecosystems., Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg. Pp. <missing location>

Griffiths, Charles, Robinson, Tamara; Mead, Angela (2011) In the wrong place- Alien marine crustaceans: Distribution, biology, impacts, Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands. Pp. 269-282

Harrison, K.; Ellis, J. P. (1991) The genera of the Sphaeromatidae (Crustacea: Isopoda): a key and distribution list, Invertebrate Taxonomy 5: 915-952

Hewitt, Chad L.; Campbell, Marnie L. (2001) The Australian distribution of the introduced sphaeromatid isopod, Paracerceis sculpta., Crustaceana 74(9): 925-936

Hewitt, Chad; Campbell, Marnie (2010) <missing title>, Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Australia, Canberra, Australia. Pp. <missing location>

Huisman, John M.; Jones, Diana S.; Wells, Fred E.; Burton, Timothy S. (2008) Introduced marine biota in Western Australian waters., Records of the Western Australian Museum 25: 1-44

Javed, Waquar; Ahmed, Roshan (1987) On the occurrence of Paradella dianae, a genus and species of Sphaeromatidae (Isopoda, Flabellifera) in the Arabian Sea., Crustaceana 53(2): 215-217

Junoy, J.; J. Castelló (2003) Catálogo de las especies ibéricas y baleares de isópodos marinos (Crustacea: Isopoda)., Boletin Insitituto Espanol de Oceanografia 19(1-4): 293-325

Karatayev A, Claudi R, Lucy F (2012) History of Dreissena research and the ICAIS gateway to aquatic invasions research, Aquatic Invasions 7(1): 1–5

https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2012.7.1.001

Karatayev AY, Burlakova LE, Karatayev VA, Boltovskoy D (2010) Limnoperna fortunei versus Dreissena polymorpha: population densities and benthic community impacts of two invasive freshwater bivalves, Journal of Shellfish Research 29(4): 975–984

https://doi.org/10.2983/0730-8000\(2007\)26[205:TIBDPA]2.0.CO;2

Li, Li (2000) A new species of Dynoides (Crustacea: Isopoda: Sphaeromatidae) from the Cape d’Aguilar Marine Reserve, Hong Kong, Records of the Australian Museum 52: 137-149

Lutaenko, Konstantin A.; Furota,Toshio; Nakayama, Satoko; Shin, Kyoungsoon; Xu, Jing (2013) <missing title>, Northwest Pacific Action Plan- Data and Information Network Regional Activity Center, Beijing, China. Pp. <missing location>

Mead, A.; Carlton, J. T.; Griffiths, C. L. Rius, M. (2011b) Introduced and cryptogenic marine and estuarine species of South Africa, Journal of Natural History 39-40: 2463-2524

Menzies, Robert J. (1962a) The marine isopod fauna of Bahia de San Quintin,Baja California, Mexico, Pacific Naturalist 3(11): 337-348

Miller, Milton A. (1968) Isopoda and Tanaidacea from buoys in coastal waters of the continental United States, Hawaii, and the Bahamas (Crustacea), Proceedings of the United States National Museum 125(3652): 1-53

Montalto L, Ezcurra de Drago I (2003) Tolerance to desiccation of an invasive mussel, Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker, 1857) (Bivalvia, Mytilidae), under experimental conditions, Hydrobiologia 498(1): 161–167

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026222414881

Montelli, Luciana; Lewis, John (2008) <missing title>, Maritime Platforms Division, Defence Science and Technology Organisation, Australia, Fishermans Bend, Victoria, Australia. Pp. 1-50

Morgan, David L.; Gill, ;Howard S.; Maddern, Mark G; Beatty. .; Stephen J. (2004) Distribution and impacts of introduced freshwater fishes in Western Australia, New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 38: 511-523

Munguia, Pablo; Shuster, Stephen M. (2013) Established populations of Paracerceis sculpta (isopoda) in the northern Gulf of Mexico, Journal of Crustacean Biology 33(1): 137-139

Pires, Ana Maria Setubal (1982) [Sphaeromatidae (Isopoda:Flabellifera) of the intertidal and shallow depths of the states of Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, Boletim do Instituto Oceanográfico 31(2): 43-55

Ribeiro, Romeu S.; Mata, Ana M. T. ; Salgado, Ricardo; Gandra, Vasco; Afonso, Inês; Galhanas, Dina; Dionísio, Maria Ana; Chainho, Paula (2023) Undetected non-indigenous species in the Sado estuary (Portugal), a coastal system under the pressure of multiple vectors of introduction, Journal of Coastal Conservation 27(53): Published online

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-023-00979-3

Rifi, Mouna; Basti, Leila; Rizzo, Lucia; Tanduo, Valentina; Radulovici, Adriana; Jaziri, Sabri; Uysal, Irfan; Souissi, Nihel; Mekki, Zeineb; Crocetta. Fabio (2023) Tackling bioinvasions in commercially exploitable species through interdisciplinary approaches: A case study on blue crabs in Africa’s Mediterranean coast (Bizerte Lagoon, Tunisia, Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 291(108419): Published online

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2023.108419

Rodriguez, A.; Drake, P.; Aris, A. M. (1992) First records of Paracerceis sculpta (Holmes, 1904) and Paradella dianae (Isopoda, Sphaeromatidae) at the Atlantic Coast of Europe,, Crustaceana 63(1): 94-97

Ruiz, Gregory M.; Geller, Jonathan (2018) Spatial and temporal analysis of marine invasions in California, Part II: Humboldt Bay, Marina del Re, Port Hueneme, and San Francisco Bay, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center & Moss Landing Laboratories, Edgewater MD, Moss Landing CA. Pp. <missing location>

Santos, Cinthya S. G. (2007) Nereididae from Rocas Atoll (North-East, Brazil)., Arq. Mus. Nac., Rio de Janeiro 65(3): 369-380

Soors, Jan; Faasse, Marco; Stevens, Maarten; Verbessem, Ingrid; De Regge, Nico;Van den Bergh, Ericia (2010) New crustacean invaders in the Schelde estuary (Belgium), Belgian Journal of Zoology 140: 3-10

Tlig-Zouari, S.; Mami, T.; Maamouri, F. (2009) Structure of benthic macroinvertebrates and dynamics in the northern lagoon of Tunis, Journal of the Marine Biological Association 89(7): 1305-1318

U.S. National Museum of Natural History 2002-2021 Invertebrate Zoology Collections Database. http://collections.nmnh.si.edu/search/iz/

Ulman, Aylin and 17 authors (2017) A massive update of non-indigenous species records in Mediterranean marinas, PeerJ 5( e3954): <missing location>

Wiltshire, K.; Rowling, K.; Deveney, M. (2010) <missing title>, South Australian Research and Development Institute, Adelaide. Pp. 1-232

Yu, Yanan' Gao, Qi; Liu, Mengling; Li, Jingqi; Wang, Shuo; Zhang, Junlong (2023) Report on the invasive American brackish-water mussel Mytella strigata (Hanley, 1843) (Mollusca: Mytilidae) in Beibu Gulf, BioInvasions Records <missing volume>: Published online

Zambrano, René; Ramos, John (2021) Alien crustacean species recorded in Ecuador, Nauplius 29: e2021043