Invasion History

First Non-native North American Tidal Record: 2000First Non-native West Coast Tidal Record:

First Non-native East/Gulf Coast Tidal Record: 2000

General Invasion History:

The sea anemone Sagartia elegans is native to Europe, ranging from Trondheim, Norway and the Faroe Islands, through the British Isles, south to Spain. It is also found in the Mediterranean Sea, including the western basin, the Adriatic, and the Aegean Sea. It occurs in the sublittoral zone from 0 to 50 m (Hayward and Ryland 1990; Coll et al. 2010; den Hartog and Ates 2011). Its occurrence in the Netherlands has been sporadic, affected by severe winters (Ates et al. 1998). The only reported introduction is a persistent population on the coast of Massachusetts, in Salem Harbor (MIT Sea Grant 2003; Pederson et al. 2005; MacIntyre et al. 2011).

North American Invasion History:

Invasion History on the East Coast:

In 2000, a population of S. elegans was found at Hawthorne Cove Marina, in Salem Harbor, MA (Massachusetts Bay) (MIT Sea Grant 2003; Pederson et al. 2005). The population has persisted, becoming inconspicuous in the winter, but regrowing in warmer weather. It has been seen as recently as 2010 (MacIntyre 2011; MIT Sea Grant 2012). It disappeared during the severe winter of 2010. Experiments with populations maintained in culture indicate that asexual reproduction ceases at 10°C, with extensive mortality at 6 °C (Wells 2013).

Description

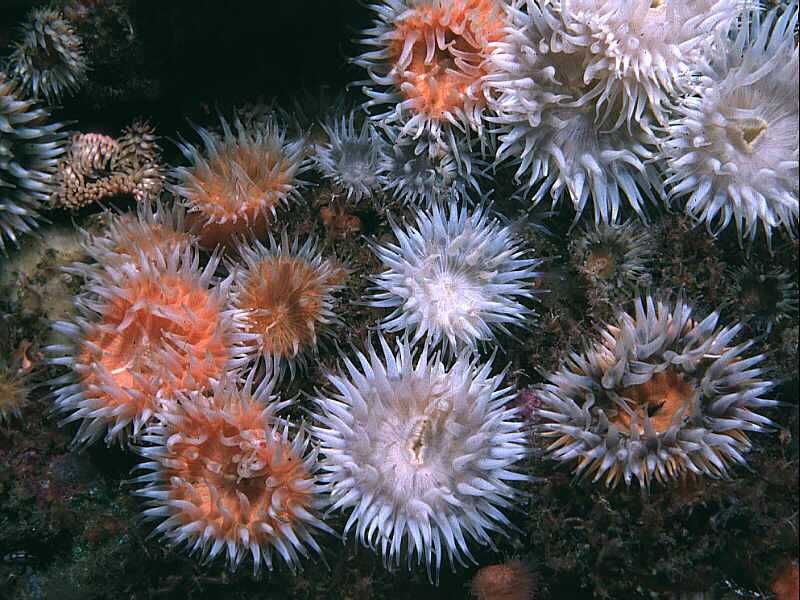

The sea anemone Sagartia elegans has a base wider than its column. The column is ~3X taller than it is wide, when extended (based on illustration), and flares toward the broad oral disk. The column is dotted with small white adhesive organs (suckers), especially toward the oral end, but these rarely have debris stuck to them. This anemone has acontia, threadlike structures, lined with cnidocytes (cells bearing nematocysts) which extend from the middle lobes of incomplete mesenteries, which partially divide the gastrovascular cavity. The acontia can be extended into the body cavity, or extruded through pores, as a defense in response to disturbance or handling. This anemone has up to 200 tentacles of moderate length. Tentacles are often irregularly arrayed, as a result of frequent pedal laceration (shedding off portions of the pedal disc, which grow into a new individual). The base is up to 30 mm in diameter, and the column may reach 90 mm. Tentacles, when extended, span up to 60 mm (description from: Hayward and Ryland 1990; MarLin 2012).

Five color patterns were formerly given status as 'varieties' in European waters. Individuals of the only introduced population in North American waters, photographed in Massachusetts, correspond to variety rosacea, with rose-pink or magenta tentacles, while the body is variable in color (Pederson et al. 2005; Hayward and Ryland 1990). Other common color patterns seen in European waters are: nivea - disk and tentacles white; venusta - orange disk, white tentacles; aurantia - variable disk color, orange tentacles; miniata - disk and tentacles with patterns, bars of orange and white (Hayward and Ryland 1990).

There has been some uncertainty about the identity of the anemone idenitified as S. elegans in Salem Harbor, Massachusetts. yhe population is now believed to be extinct (Wells 2013).

Taxonomy

Taxonomic Tree

| Kingdom: | Animalia | |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria | |

| Class: | Anthozoa | |

| Subclass: | Hexacorallia | |

| Order: | Actiniaria | |

| Suborder: | Thenaria | |

| Family: | Sagartiidae | |

| Genus: | Sagartia | |

| Species: | elegans |

Synonyms

Actinia miniata (Gosse, 1853)

Sagartia rhododactylus (None, None)

Potentially Misidentified Species

Ecology

General:

Sea anemones of the genus Sagartia can reproduce sexually by releasing eggs and sperm into the water, and asexually by longitudinal fission, or by a method called pedal laceration. In pedal laceration, as the anemone moves, a portion of its base is left behind and grows into a new anemone (Barnes 1983). In S. elegans the arrangement of the tentacles is often irregular, due to the frequent occurrence of pedal laceration, in which a portion of the body may be budded off (Hayward and Ryland 1990; Ates et al. 1998).

This anemone is known from rocky coasts and harbors, where it grows in rock pools, under stones, on seaweeds, breakwaters, pilings, and floats. It has also been collected from clay and gravel bottoms. It often occurs in cracks and crevices, where only its tentacles protrude (Hayward and Ryland 1990; Ates et al. 1998). Like other anemones, it feeds by trapping zooplankton and small epibenthic animals on its tentacles (Barnes 1983). On the Dutch coast, it was found only at salinities above 28 PSU (Braber and Borghouts 1977). Ates et al. (1998) suggest that it is prone to mortality when water temperatures drop below 2°C. In Salem Harbor, Massachusetts, it is hard to find in the winter, but regrows in the summer (MIT Sea Grant 2003). This population persisted until 2010, but disappeared duning the severe winter of 2010-2011. Experiments with cultured animals supported the hypothesis that prolonged low temperatures contributed to the extinction of the population (Wells 2013).

Food:

Zooplankton, small epibenthos

Trophic Status:

Carnivore

CarnHabitats

| General Habitat | Rocky | None |

| General Habitat | Marinas & Docks | None |

| Salinity Range | Polyhaline | 18-30 PSU |

| Salinity Range | Euhaline | 30-40 PSU |

| Tidal Range | Low Intertidal | None |

| Tidal Range | Subtidal | None |

| Vertical Habitat | Epibenthic | None |

Tolerances and Life History Parameters

| Minimum Temperature (ºC) | 6 | Extensvie mortality of cultured animals at this temperature Wells 2013). |

| Minimum Salinity (‰) | 20 | Experiments with cultured animals (Wells 2013) |

| Broad Temperature Range | None | Cold temperate-Warm temperate |

| Broad Salinity Range | None | Polyhaline-Euhaline |

General Impacts

No ecological or economic impacts have been reported for S. elegans in its native or introduced range.Regional Distribution Map

Non-native

Native

Cryptogenic

Failed

Occurrence Map

References

Appeltans, W. et al. 2011-2015 World Registry of Marine Species. <missing URL>Ates, R. M. L.; Dekker, R.; Faasse, M. A.; den Hartog, J. C. (1998) The occurrence of Sagartia elegans (Dalyell, 1848) (Anthozoa: Actiniaria) in the Netherlands, Zoologische Verhandelingen 323: 263-276

Barnes, Robert D. (1983) Invertebrate Zoology, Saunders, Philadelphia. Pp. 883

Braber, L.; Borghouts, H. (1977) Distribution and ecology of Anthozoa in the estuarine region of the rivers Rhine, Meuse and Scheldt., Hydrobiologia 52(1): 15-20

Coll, Marta and 36 authors (2010) The biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: Estimates, patterns, and threats, None 5(8): e11842

de Montaudouin, Xavier; Sauriau, Pierre-Guy (2000) Contributions to a synopsis of marine species richness in the Pertuis-Charentais Sea with new insights into the soft-bottom macrofauna of the Marennes-Oleron Bay, Cahiers de Biologie Marine 41: 181-222

den Hartog, J. C.; Ates, R. M. L. (2011) Actiniaria from Ria de Arosa, Galicia, northwestern Spain, in the Netherlands Centre for Biodiversity Naturalis, Leiden, Zoologische Mededelingen 85: 11-53

Gimenez, Lucas H.; Brante, Antonio (2021) Do non-native sea anemones (Cnidaria: Actiniaria) share a common invasion pattern? – A systematic review, Aquatic Invasions 16: 365-390

Glon, Heather; Daly, Marymega; Carlton, . James, T.; Flenniken, Megan M.; Currimjee, Zara (2020) Mediators of invasions in the sea: life history strategies; and dispersal vectors facilitating global sea anemone introductions, Biological Invasions 22: pages3195–3222

Gosner, Kenneth L. (1978) A field guide to the Atlantic seashore., In: (Eds.) . , Boston. Pp. <missing location>

Hayward, P.J.; Ryland, J. S. (1990) The Marine Fauna of the British Isles and North-West Europe, 1 Clarendon Press, Oxford. Pp. <missing location>

MacIntyre, Chris; Adrienne Pappal; Pederson, Judy; Smith, Jan P. (2011) Marine Invaders in the Northeast Rapid Assessment Survey of non-native and native marine species of floating dock communities, Massachusetts Coastal Zone Management, Boston MA. Pp. <missing location>

MarLin- Marine Life Information Network 2006-2024 MarLin- Marine Life Information Network. <missing URL>

Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management (2013) Rapid assessment survey of marine species at New England floating docks and rocky shores, Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management, Boston MA. Pp. <missing location>

MIT Sea Grant 2003-2008 Introduced and cryptogenic species of the North Atlantic. <missing URL>

MIT Sea Grant 2009-2012 Marine Invader Tracking and Information System (MITIS). <missing URL>

Morton B, Leung KF (2015) Introduction of the alien Xenostrobus securis (Bivalvia: Mytilidae) into Hong Kong, China: Interactions with and impacts upon native species and the earlier introduced Mytilopsis sallei (Bivalvia: Dreissenidae), Marine Pollution Bulletin 92(1-2): 134-142

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.12.046

Pederson, Judith and 15 authors (2003) <missing title>, MIT Sea Grant College Program, Cambridge. Pp. <missing location>

Pettay, D. Tye Wham, Drew C. Smith, Robin T. Iglesias-Prieto, Roberto LaJeunesse, Todd C. (2015) Microbial invasion of the Caribbean by an Indo-Pacific coral zooxanthella, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 7513–7518

www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1502283112