Invasion History

First Non-native North American Tidal Record: 1874First Non-native West Coast Tidal Record: 1874

First Non-native East/Gulf Coast Tidal Record: 1949

General Invasion History:

White Catfish (Ameiurus catus) are native to Atlantic and Gulf drainages from the Hudson River to the Apalachicola River, Florida. They were introduced to the Connecticut, Charles, and Kennebec rivers in New England, and to the Pensacola and drainages on the Gulf (Page and Burr 1991; USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2014). On the West Coast, White Catfish were introduced to the Sacramento River in 1874 (Smith 1896; Cohen and Carlton 1995; Dill and Cordone 1997) and to the Columbia River in 1932 (Lampman 1946). In 1938 they were introduced to Puerto Rico (established), and unsuccessfully to the Philippines (Lever 1996).

North American Invasion History:

Invasion History on the West Coast:

In 1874 Livingstone Stone from the US Fish Commission, brought 56 White Catfish (Ameiurus catus) from the Raritan River and planted them in the Sacramento River near Stockton, California. These fish survived and spawned, and by 1877 were stocked in 12 counties in the Sacramento-San Joaquin watershed and in southern California. In 1878-1979, 30,000 White Catfish were stocked in 22 counties (Smith 1895). By 1900, there was a major commercial fishery for White Catfish in the Sacramento Delta, which was curtailed in 1953 because of fears of overfishing, but this fish remained an important sport fish (Cohen and Carlton 1995). In a 1980s survey, White Catfish were the most abundant species in the Delta between 1980-1984, and were third in 1993-1999, but dropped to tenth in rank in 2001-2003 (Feyrer and Healy 2003; Brown and Michniuk 2007). In the Yolo Bypass of the Sacramento River, at the head of the Delta, they were the most abundant fish in 1999-2006, comprising 46% of the fish sampled (Sommer et al. 2014). They commonly occur downstream in brackish Suisun Bay at salinities up to 12 PSU (Matern et al. 2002; Moyle 2002).

White Catfish are apparently established, but rare, in the Columbia River and basin. The date of their introduction into the Columbia River basin is uncertain. Unidentified 'catfish' were introduced into Silver Lake on the Cowlitz River, and reached the Columbia River (Smith 1895). In 1930, some White Catfish from California were planted in Blue Lake, near Portland, Oregon, which is adjacent to the Columbia River. A specimen was caught in the Columbia River, near Portland in 1943 (Lampman 1946) and two were caught in lower Columbia Slough, Portland in 2008-2009 (Van Dyke et al. 2009).

Invasion History on the East Coast:

White Catfish are native to the unglaciated portion of the Atlantic and easternmost Gulf Coastal Plain, north to the Hudson River estuary, but were absent from the glaciated coastal drainages of New England. They have been introduced to the Connecticut River (1960, Whitworth et al. 1968; Marcy 1976), the Thames River (CT, 1973, Whitworth 1996); the Charles River (MA, 1910-1949, Hartel 2002), the Merrimack River (1910-1949, Hartel 2002); Kennebec River-Merrymeeting Bay (2001, USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2018) and the Penobscot River (1980, USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Programs 2006). These introductions probably represent a mixture of official and informal stockings. On Florida's Gulf Coast, White Catfish are native to the Apalachicola drainage, but considered introduced to the Choctawhatchee and Pensacola Bay drainages (USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2018). A commercial fisherman reared White Catfish in a pen in Lake Erie starting in 1939. A number of these fish escaped but did not become established (Emery 1985).

Invasion History Elsewhere in the World:

White Catfish were introduced to Puerto Rico, possibly as early as 1938 in a shipment of Channel Catfish from Baltimore MD (Lever 1996). They are established in several inland reservoirs on the Island (USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2018). One albino fish, presumably a discarded ornamental fish, was caught in a pond in England in 2005, the first record of this species in Europe (Britton and Davies 2006).

Description

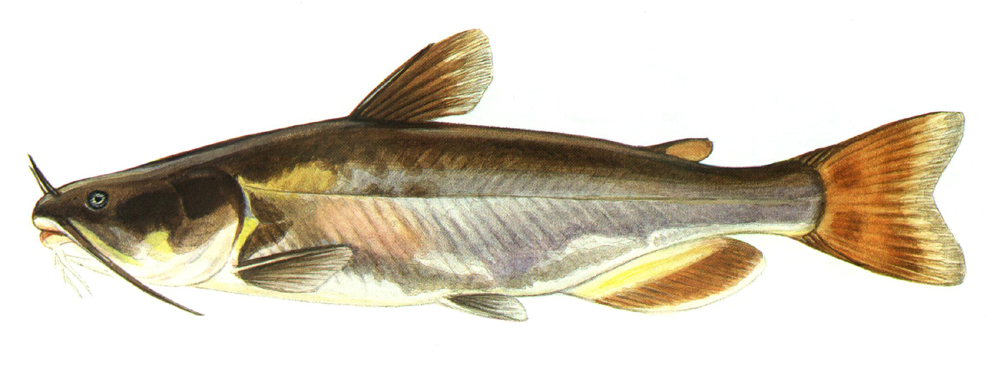

White Catfish (Ameiurus catus) are freshwater fish but are common in brackish regions of estuaries. Bullhead Catfishes (Ictaluridae) have four pairs of barbels, no scales, an adipose fin, stout spines at the origins of the dorsal and pectoral fins, and abdominal pelvic fins. The tail fin of the White Catfish is moderately forked, with rounded lobes. The base of the anal fin is relatively short, and the fin is rounded with 22-25 rays. The rear edge of the pectoral spines has 11-15 moderate saw-like teeth. The dorsal fin is relatively short, with one spine and 5-7 soft rays. The head is broad and depressed. Adults can reach 620 mm but are more usually 300 to 330 mm. White Catfish are gray-blue-black above, and white to light-yellow below, with a dusky to black adipose fin. The chin barbels are white, while the other barbels are dusky (Page and Burr 1991; Jenkins and Burkhead 1993; Murdy et al. 1997; Moyle 2002).

Taxonomy

Taxonomic Tree

| Kingdom: | Animalia | |

| Phylum: | Chordata | |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata | |

| Superclass: | Osteichthyes | |

| Class: | Actinopterygii | |

| Subclass: | Neopterygii | |

| Infraclass: | Teleostei | |

| Superorder: | Ostariophysi | |

| Order: | Siluriformes | |

| Family: | Ictaluridae | |

| Genus: | Ameiurus | |

| Species: | catus |

Synonyms

Pimelodus catus (None, None)

Silurus catus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Potentially Misidentified Species

Ameiurus melas (Black Bullhead) is native to the Mississippi-Great Lakes basin and has been introduced to the San Francisco estuary and the Columbia River. The tail is squared-off, the pectoral spine lacks saw-like teeth, and the chin barbels are dark (Page and Burr 1991).

Ameiurus natalis

Ameiurus natalis (Yellow Bullhead) is native to the Atlantic Slope and Mississippi-Great Lakes basin and has been introduced to the San Francisco estuary and the Columbia River. The tail is squared-off, the pectoral spine has saw-like teeth, and the chin barbels are white or yellow (Page and Burr 1991).

Ameiurus nebulosus

Ameiurus nebulosus (Brown Bullhead) is native to the Atlantic Slope and Mississippi-Great Lakes basin and has been introduced to the San Francisco estuary and the Columbia River and Fraser Rivers. The tail is squared-off, the pectoral spine has saw-like teeth, and the chin barbels are dark. The body has dark brown mottling (Page and Burr 1991).

Ictalurus furcatus

Ictalurus furcatus (Blue Catfish) are native to the Mississippi-Gulf Basin, and has been introduced, but is rare, in the San Francisco estuary. Adults are very large, and bluish gray in color, without dark mottling. The caudal fin is deeply forked, and the anal fin has a straight edge but is tapered posteriorly (Page and Burr 1991).

Ictalurus punctatus

Ictalurus punctatus (Channel Catfish) are native to the Mississippi-Gulf Basin, and the southeastern Coastal Plain, and has been introduced to the San Francisco estuary and the Columbia River. Adults are large, gray in color, without scattered dark spots. The caudal fin is deeply forked, and the anal fin has a curved edge (Page and Burr 1991).

Ecology

General:

White Catfish (Ameiurus catus) are freshwater fish that often occur in estuaries. Male and female catfish do not have obvious morphological differences. They mature in 1-2 years, at 152-211 mm (Jones et al. 1978). Spawning occurs at 21-30 C in nests built near sand or gravel banks (Jones et al. 1978). The nests are up to 0.9 m across and 0.45 m deep. Wang (1986) reported nests 'in hollowed tubes, large cans, crevices or cement or rocky jetties'. Females contain 1000-3500 eggs. During spawning, the male and female embrace in a head-to-tail fashion, with the males' tail curled around the female's head. The eggs are very adhesive and laid in small clusters. They are usually guarded by the male, but sometimes by both parents. They take 6-7 days to hatch at 24-29 C (Jones et al. 1978; Jenkins and Burkead 1994). Prolarvae remain in the nest until the yolk-sac is absorbed. When the yolk-sac is absorbed, fin-ray development is complete, and the fish are juveniles, starting at ~14 mm. Juveniles swim in dense schools in shallow water (Jones et al. 1978; Wang 1986).

White Catfish (Ameiurus catus) range from cold-temperate to subtropical climates and tolerate temperatures from near 0 C in ice-covered rivers in winter, to 31 C (Kendall and Schwartz 1968; Page and Burr 1991). Adults tolerate salinities up to 14 PSU in the laboratory and have been reported at 12 to 14.5 PSU in the field (Kendall and Schwartz 1968; Jones et al. 1978; Murdy et al. 1997). Their habitats include 'sluggish, mud-bottomed pools, open channels, and backwaters of small to large rivers’, and fresh to brackish portions of estuaries (Wang 1986; Page and Burr 1991). White catfish are omnivorous and eat aquatic plants, benthic invertebrates, and small fishes. In the San Francisco estuary, young fish (~40 mm long) feed on corophiid amphipods, mysids, and chironomid midge larvae. As they grow, they include larger invertebrates, carrion, and fishes, but still feed largely on invertebrates (Moyle 2002). Surprisingly, growth rates of White Catfish in the Delta are slow, compared to East Coast and California lake/river populations, possibly because of a dense population, or a lack of forage fish (Schafter et al. 1997). Predators include larger fish, birds, and humans.

Food:

Aquatic plants; benthic invertebrates, fishes

Consumers:

fishes, birds, humans

Trophic Status:

Omnivore

OmniHabitats

| General Habitat | Nontidal Freshwater | None |

| General Habitat | Fresh (nontidal) Marsh | None |

| General Habitat | Grass Bed | None |

| General Habitat | Coarse Woody Debris | None |

| General Habitat | Swamp | None |

| General Habitat | Tidal Fresh Marsh | None |

| General Habitat | Salt-brackish marsh | None |

| General Habitat | Unstructured Bottom | None |

| Salinity Range | Limnetic | 0-0.5 PSU |

| Salinity Range | Oligohaline | 0.5-5 PSU |

| Salinity Range | Mesohaline | 5-18 PSU |

| Tidal Range | Subtidal | None |

| Vertical Habitat | Nektonic | None |

Life History

Tolerances and Life History Parameters

| Minimum Temperature (ºC) | 4 | Occurs in ice-covered water, eg. Hudson River |

| Maximum Temperature (ºC) | 31 | Experimental, acclimated to 20 C (Jones et al. 1978) |

| Minimum Salinity (‰) | 0 | A freshwater species |

| Maximum Salinity (‰) | 14.5 | Field data (Schwartz 1965) |

| Minimum Reproductive Temperature | 21 | Field data (Jones et al. 1978) |

| Maximum Reproductive Temperature | 30 | Field data (Jenkins and Burkhead 1994) |

| Minimum Reproductive Salinity | 0 | A freshwater species |

| Minimum Length (mm) | 152 | Mature at 152-211 mm (Jones et al. 1978) |

| Maximum Length (mm) | 610 | Jones et al. 1978 |

General Impacts

White Catfish (Ameiurus catus), together with other catfishes, are an important fishery species in their native range and in the San Francisco Bay estuary (Menzel 1945; Dill and Cordone 1997). While they are an abundant generalized predator on invertebrates and small fishes, there are no specific impacts of their introduction.

Economic Impacts

Fisheries- By 1880, six years after the introduction of the White Catfish to the San Francisco estuary, a substantial fishery was established. Smith (1896) quotes the California fish commissioners' report: 'The produce of the few fish of this species, imported in 1874, now annually furnishes a large and valuable supply of fish food to people in the interior of the State. The value of all the fish of this species now caught annually and consumed as food would more than equal the annual appropriation made by the State and placed at the disposal of the fish commissioners. In 1953, the commercial fishery was ended, because of fear of overfishing (Cohen and Carlton 1995). White Catfish continue to be an important warmwater sport fish in California, though it may be overtaken by Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), which are larger, and easier to catch (Moyle 2002).

Regional Impacts

| P090 | San Francisco Bay | Economic Impact | Fisheries | ||

| By 1877, White Catfish supported a significant commercial fishery in the San Francisco Bay estuary (Smith 1896). In 1953, the commercial fishery was ended, because of overfishing, but it remains an important sportfish (Cohen and Carlton 1995; Dill and Cordone 1997). | |||||

| CA | California | Economic Impact | Fisheries | ||

| By 1877, White Catfish supported a significant commercial fishery in the San Francisco Bay estuary (Smith 1896). In 1953, the commercial fishery was ended, because of overfishing, but it remains an important sportfish (Cohen and Carlton 1995; Dill and Cordone 1997). | |||||

Regional Distribution Map

Non-native

Native

Cryptogenic

Failed

| Bioregion | Region Name | Year | Invasion Status | Population Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GL-II | Lake Erie | 1939 | Non-native | Failed |

| P260 | Columbia River | 1930 | Non-native | Established |

| M040 | Long Island Sound | 1960 | Non-native | Established |

| N150 | Merrimack River | 1949 | Non-native | Established |

| N170 | Massachusetts Bay | 1949 | Non-native | Established |

| P090 | San Francisco Bay | 1874 | Non-native | Established |

| M060 | Hudson River/Raritan Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| M090 | Delaware Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| M130 | Chesapeake Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| S010 | Albemarle Sound | 0 | Native | Established |

| S020 | Pamlico Sound | 0 | Native | Established |

| S030 | Bogue Sound | 0 | Native | Established |

| S050 | Cape Fear River | 0 | Native | Established |

| S060 | Winyah Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| S070 | North/South Santee Rivers | 0 | Native | Established |

| S080 | Charleston Harbor | 0 | Native | Established |

| S090 | Stono/North Edisto Rivers | 0 | Native | Established |

| S110 | Broad River | 0 | Native | Established |

| S100 | St. Helena Sound | 0 | Native | Established |

| S120 | Savannah River | 0 | Native | Established |

| S130 | Ossabaw Sound | 0 | Native | Established |

| S140 | St. Catherines/Sapelo Sounds | 0 | Native | Established |

| S150 | Altamaha River | 0 | Native | Established |

| S160 | St. Andrew/St. Simons Sounds | 0 | Native | Established |

| S170 | St. Marys River/Cumberland Sound | 0 | Native | Established |

| S180 | St. Johns River | 0 | Native | Established |

| S183 | _CDA_S183 (Daytona-St. Augustine) | 0 | Native | Established |

| S190 | Indian River | 0 | Native | Established |

| S196 | _CDA_S196 (Cape Canaveral) | 0 | Native | Established |

| S200 | Biscayne Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| G010 | Florida Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| G020 | South Ten Thousand Islands | 0 | Native | Established |

| G030 | North Ten Thousand Islands | 0 | Native | Established |

| G045 | _CDA_G045 (Big Cypress Swamp) | 0 | Native | Established |

| G050 | Charlotte Harbor | 0 | Native | Established |

| G070 | Tampa Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| G074 | _CDA_G074 (Crystal-Pithlachascotee) | 0 | Native | Established |

| G078 | _CDA_G078 (Waccasassa) | 0 | Native | Established |

| G076 | _CDA_G076 (Withlachoochee) | 0 | Native | Established |

| G080 | Suwannee River | 0 | Native | Established |

| G086 | _CDA_G086 (Econfina-Steinhatchee) | 0 | Native | Established |

| G090 | Apalachee Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| G100 | Apalachicola Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| G110 | St. Andrew Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| G130 | Pensacola Bay | 1954 | Non-native | Established |

| G120 | Choctawhatchee Bay | 0 | Native | Established |

| G150 | Mobile Bay | 1996 | Non-native | Established |

| N090 | Kennebec/Androscoggin River | 2001 | Non-native | Established |

| N050 | Penobscot Bay | 1980 | Non-native | Unknown |

| NEP-IV | Puget Sound to Northern California | 1930 | Non-native | Established |

| NA-ET3 | Cape Cod to Cape Hatteras | 1949 | Non-native | Established |

| NA-ET2 | Bay of Fundy to Cape Cod | 1949 | Non-native | Established |

| NEP-V | Northern California to Mid Channel Islands | 1874 | Non-native | Established |

| CAR-VII | Cape Hatteras to Mid-East Florida | 0 | Native | Established |

| CAR-I | Northern Yucatan, Gulf of Mexico, Florida Straits, to Middle Eastern Florida | 1954 | Non-native | Established |

Occurrence Map

| OCC_ID | Author | Year | Date | Locality | Status | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|

References

Kim, Daemin; Taylor, Andrew T.; Near, Thomas J. (2022) Phylogenomics and species delimitation of the economically important Black Basses (Micropterus), Scientific Reports 12(9112): Published onlinehttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11743-2

Sotka, Erik E.; Bell; Tina; Hughes, Laurn E. ; Lowry, James K.; Poore, Alistair G. B. (2016) A molecular phylogeny of marine amphipods in the herbivorous family Ampithoidae, Zoologica Scripta 46(1): 85-95

doi:10.1111/zsc.12190

Sotka, Erik E.; Bell; Tina; Hughes, Laurn E. ; Lowry, James K.; Poore, Alistair G. B. (2016) A molecular phylogeny of marine amphipods in the herbivorous family Ampithoidae, Zoologica Scripta 46(1): 85-95

doi:10.1111/zsc.12190

Bangs, Max R.; Oswald, Kenneth J.; Greig, Thomas W.; Leitner, Jean K.; Rankin, Daniel M.; Quattro, Joseph M. (2018) Introgressive hybridization and species turnover in reservoirs: a case study involving endemic and invasive basses (Centrarchidae: Micropterus) in southeastern North America, Conservation Genetics 19: 57-69

DOI 10.1007/s10592-017-1018-7

Bond, Carl E., Rexstad, Eric, Hughes, Robert M. (1988) Habitat use of tweny-five common species of Oregon freshwater fishes, Northwest Science 62(5): 223-232

Brown, Larry R.; Michniuk, Dennis (2007) Littoral fish assemblages of the alien-dominated Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, 1980-1983 and 2001-2003., Estuaries and Coasts 90: 186-200

Cavallo, Bradley; Merz, Joseph; Setka, Jose (2013) Effects of predator and flow manipulation on Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) survival in an imperiled estuary, Environmental Biology of Fishes 393: 393-403

Chapman, Wilbert M. (1942) Alien fishes in the waters of the Pacific Northwest, California Fish and Game 28: 9-15

Cohen, Andrew N.; Carlton, James T. (1995) Nonindigenous aquatic species in a United States estuary: a case study of the biological invasions of the San Francisco Bay and Delta, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Sea Grant College Program (Connecticut Sea Grant), Washington DC, Silver Spring MD.. Pp. <missing location>

Cook Inlet Regional Citizen's Council 2023 Seaweeds of Alaska. https://www.seaweedsofalaska.com/species.asp?SeaweedID=46

Dill, William A.; Cordone, Almo J. (1997) History and status of introduced fishes in California, 1871-1996, California Department of Fish and Game Fish Bulletin 178: 1-414

Emery, Lee (1985) Review of fish species introduced into the Great Lakes, 1819-1974., Great Lakes Fisheries Commission 45: 1-31

Farr, Ruth A., Ward, David L. (1992) Fishes of the lower Willamette River, near Portland, Oregon, Northwest Science 67(1): 16-22

Feyrer, Frederick; Healey, Michael P. (2003) Fish community structure and environmental correlates in the highly altered southern Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta., Environmental Biology of Fishes 66: 123-132

Hargrove . John S.; Weyl, Olaf L. F.; Austin, James D. (2017) Reconstructing the introduction history of an invasive fish predator in South Africa, Biological Invasions 19: 2261–2276

doi:10.1007/s10530-017-1437-x)

Hartel, Karsten E.; Halliwell, David B.; Launer, Alan E. 1996 An annotated working list of the inland fishes of Massachusetts. <missing URL>

Hartel, Karsten E.; Halliwell, David B.; Launer, Alan E. (2002) Inland Fishes of Massachusetts, Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln MA. Pp. 328 pp.

Hughes, Robert M., Gammon, James R. (1987) Longitudinal changes in fish assemblages and water quality in the Willamette River, Oregon, Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 116: 196-209

Huntsman, Brock M.; Young, Matthew J.; Feyrer, Frederick V. ; Stumpner, Paul R. ; Brown, Larry R.; Burau, Jon R. (2023) Hydrodynamics and habitat interact to structure fish communities within terminal channels of a tidal freshwater delta, Ecosphere 14(e4339): Published online

DOI: 10.1002/ecs2.4339

Jacobson, Paul M. (1980) Studies of the Ichthyofauna of Connecticut, Storrs Agricultural Experiment Station. Papers 82: 1-39

Jenkins, Robert E.; Burkhead, Noel M. (1993) Freshwater Fishes of Virginia, American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, MD. Pp. <missing location>

Jones, Philip W.; Martin, F. Douglas; Hardy, Jerry D., Jr. (1978) Development of fishes of the mid-Atlantic Bight. V. 1. Acipenseridae through Ictaluridae., In: (Eds.) . , Washington DC. Pp. <missing location>

Keller, David H. (2011) Population characteristics of white catfish and channel catfish in the Delaware River estuary, American Fisheries Society Symposium 77: 423-436

Lampman, Ben Hur (1946) Coming of the Pond Fishes, Binfords & Mort, Portland, OR. Pp. <missing location>

Lee, David S.; Gilbert, Carter R.; Hocutt, Charles H.; Jenkins, Robert E.; McAllister, Don E.; Stauffer, Jay R. (1980) Atlas of North American freshwater fishes, North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, Raleigh. Pp. <missing location>

Lever, Christopher (1996) Naturalized fishes of the world, Academic Press, London, England. Pp. <missing location>

Marcy, Barton C., Jr. (1976) Fishes of the lower Connecticut River and the effects of the Connecticut Yankee Plant, American Fisheries Society Monograph 1: 61-113

Matern, Scott A.; Moyle, Peter; Pierce, Leslie C. (2002) Native and alien fishes in a California estuarine marsh: twenty-one years of changing assemblages, Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 131: 797-816

Menzel, R. Winston (1943) The catfish fishery of Virginia, Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 73: 363-373

Murdy, Edward O.; Birdsong, Ray S.; Musick, John A. (1997) Fishes of Chesapeake Bay, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.. Pp. 57-289

Page, Lawrence M.; Burr, Brooks M. (1991) Freshwater Fishes: North America North of Mexico, Houghton-Mifflin, Boston. Pp. <missing location>

Sakaris, Peter C. ; Bonvechio, Timothy F. ; Bowen, Bryant R. (2017) Relative Abundance, Growth, and Mortality of the White Catfish, Ameiurus catus L., in the St. Marys River, Southeastern Naturalist 16(3): 331-342

https://doi.org/10.1656/058.016.0319

Schwartz, Frank J. (1965) Natural salinity tolerances of some freshwater fishes, Underwater Naturalist 2(2): 13-15

Shebley, W. H. (1917) Introduction of food and game fishes into the waters of California., California Fish and Game 3(1): 1-12

Simon, Carol A.; van Niekerk, H. Helene; Burghardt, Ingo; ten Hove, Harry A.; Kupriyanova, Elena K. (2019) Not out of Africa: Spirobranchus kraussii (Baird, 1865) is not a global fouling and invasive serpulid of Indo-Pacific origin, Biological Invasions 14(3): 221–249.

Smith, Hugh M. (1895) A review of the history and results of the attempts to acclimatize fish and other water animals in the Pacific states., Bulletin of the U. S. Fish Commission 15: 379-472

Spies, Brenton Tyler (2022) Conservation and Metapopulation Management of the Federally Endangered Tidewater Gobies (Genus Eucyclogobius), University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles. Pp. <missing location>

Sytsma, Mark D.; Cordell, Jeffrey R.; Chapman, John W.; Draheim, Robyn, C. (2004) <missing title>, Center for Lakes and Reservoirs, Portland State University, Portland OR. Pp. <missing location>

USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Program 2003-2024 Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database. https://nas.er.usgs.gov/

Wang, Johnson C. S. (1986) Fishes of the Sacramento - San Joaquin Estuary and Adjacent Waters, California: A Guide to the Early Life Histories, IEP Technical Reports 9: 1-673

Whitworth, Walter R. (1968) Freshwater fishes of Connecticut, Bulletin, State Geological and Natural History Survey of Connecticut 101: 1-134

Whitworth, Walter R. (1996) Freshwater fishes of Connecticut, State Geological and Natural History Survey of Connecticut 114: 33-214

Wright, Rosalind; et al. (2022) First direct evidence of adult European eels migrating to their breeding place in the Sargasso Sea, Scientific Reports 3,2(25362): Published online

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19248-8

Zeng, Cong; Tang, Yangxin; Vastrade, Martin; Coughlan, Neil E; Zhang. Ting; Cai, Yongjiu; Van Doninck, Karine; Li, Deliang (2022) Salinity appears to be the main factor shaping spatial COI diversity of Corbicula lineages within the Chinese Yangtze River Basin, Diversity and Distributions <missing volume>: Published online

DOI: 10.1111/ddi.13666